Kryptonite for humans

Edit: Conjuction fallacy to Conjunction fallacy (Thanks Barry!)

In this post, we will stop and ponder over the question, “What is that makes us human, supposedly a complete being?”. Puzzling limitation of our mind: our excessive confidence in what we believe we know, and our apparent inability to acknowledge the full extent of our ignorance and the uncertainty of the world we live in.

Everyday we hear left and right about “how AI will suprass human intelligence, AI will be more human-like and on and on…”. We are just shown the good side of being human but there is another side about what makes us humans. How familiar are to that side? How much do we understand what is that makes us humans? Will AI really beat humans, understand humans?

To be a good diagnostician, a physician needs to acquire a large set of labels for diseases, each of which binds an idea of the illness and its symptoms, possible antecedents and causes, possible developments and consequences, and possible interventions to cure or mitigate the illness. Learning medicine consists in part of learning the language of medicine. A deeper understanding of human minds, their judgements and choices also requires a richer vocabulary than is available in everyday language. Much of this post aims to improve the ability to identify and understand errors of judgement and choice, in others and eventually in ourselves, by providing a richer and more precise language to discuss them.

We have came so far but when it comes to understanding ourselves we know so little about ourselves and others.

This post will be a collection of thoughts shamelessly stolen from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow, Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Rationality : A-Z(free read), Nassim Taleb’s Black Swan, Charlie Munger’s The Psychology of Human Misjudgment(free read) and Sanjay Bakshi’s classes on Behavioral Finance and Business Valuation(free to read).

Eliezer Yudkowsky explains in What Do We Mean By “Rationality”? the rational behind the all-famous site “Less Wrong”,

This is why there is a whole site called “Less Wrong,” rather than a single page that simply states the formal axioms and calls it a day. There’s a whole further art to finding the truth and accomplishing value from inside a human mind: we have to learn our own flaws, overcome our biases, prevent ourselves from self-deceiving, get ourselves into good emotional shape to confront the truth and do what needs doing, et cetera, et cetera.

Charlie Munger in “The Psychology of Human Misjudgement” states,

Man is often fooled, either by the cleverly thought out manipulation of man, by circumstances occuring by accident, or by very effective manipulation practices that man has stumbled into during “practice evolution” and kept in place because they work so well.

One such outcome is caused by a quantum effect in human perception. If stimulus is kept below a certain level, it does not get through. And, for this reason, a magician was able to make the Statue of Liberty disappear after a certain amount of magician lingo expressed in the dark. The audience was not aware that it was sitting on a platform that was rotating so slowly, below man’s sensory threshold, that no one could feel the acceleration implicit in the considerable rotation. When a surrounding cutrain was then opened in the place on the platform where the Statue had earlier appeared, it seemed to have disappeared.

Anchoring Effect

It occurs when people consider a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity. In many situayions, people make estimates by starting from an initial value that is adjusted to yield the final answer. Different starting points yield different estimates, which are biased toward the initial values. This phenomenon is called anchoring.

In an experiment Kahneman and Tversky had their subjects spin a wheel of fortune. The subjects first looked at the number on the wheel, which they knew was random, then they were asked to estimate the number of African countries in United Nations. Those who had a low number on the wheel estimated a low number of African nations; those with a high number produced a higher estimate.

Affect Heuristic

People let their likes and dislikes determine their beliefs about the world. People make judgements and decisions consulting their emotions. If you like current health policy, you believe its benefits are substantial and its costs are more manageable than the costs of alternatives.

Authority-Misinfluence Tendency

Man was born mostly to follow leaders, with only a few people doing the leading. And so, human society is formally organized into dominance hierarchies, with their culture augmenting the natural follow-the-leader tendency of man. Man is often destined to suffer greatly when the leader is wrong or when his leader’s ideas don’t get through properly in the bustle of life and are misunderstood. And so, we find much miscognition from man’s Authority-Misinfluence Tendency.

Other versions of confused instructions from authority figures are tragic. In World War II, a new pilot for a general, who sat beside hum in the copilot’s seat, was so anxious to please his boss that he misterpreted some minor shift in the general’s position as a direction to do some foolish thing. The pilot crashed the plane and became a paraplegic. Stanely Milgram decided to do an experiment to determine exactly how far authority figures could lead ordinary prople into gross misbehavior. In this experiment, a man posing as an authority figure, namely a professor govering a respectable experiment, was able to trick a great many ordinary people into giving what they had every reason to believe were massive electric shocks that inflicted heavy torture on innocent fellow citizens. This experiment did demonstrate a terrible result contributed to by Authority-Misinfluence Tendency, but it also demonstrated extreme ignorance in the pyschology professoriate right after World War II.

A pyschology Ph.D. once became a CEO of a major company and went wild, creating an expensive headquarters, with a great wine cellar, at an isolated site. At some point, his underlings remonstrated that money was running short. “Take money out of the depreciation reserves,” said the CEO. Not too easy because a depreciation reserve is a liability account.

So strong is undue respect for authority that this CEO, and many even worse examples, have actually been allowed to remain in control of important business institutions for long periods after it was clear they should be removed. The obvious implication: be careful whom you appoint to power because a dominant authority figure will often be hard to remove, aided as he will be by Authority-Misinfluence Tendency.

Availiablity bias or Availability-Misweighing Tendency

In a famous study, spouses were asked, “How large was your personal contribution to keeping the place tidy, in percentages?” They also answered similar questions about “taking out garbages,” “initiating social engagements”, etc. Would the self-estimated contributions add up to 100%, or more, or less? As expected, the self-assessed contributions added up to more than 100%. The explaination is a simple availability bias: both spouses remember their own individual efforts and contributions much more clearly than those of the other,and the difference in availability leads to difference in judged frequency. The same bias contributes to common observation that many members of a collaborative team feel they have done more than their share and also feel that the others are not adequately grateful for their individual contributions. Man’s imperfect, limited-capacity brain easily drifts into working with what’s easily available to it.

A professor in UCLA found an ingenious way to exploit the availability bias. He asked different groups of students to list ways to improve the course, and he varied the required number of improvements. As expected, the students who listed more ways to improve the class rated it higher.

Availability cascade

An availability cascade is a slef-sustaining chain of events, which may start from media reports of a relatively minor event and lead up to public panic and large-scale government action.

In today’s world, terrorists are the most significant practitioners of the art of inducing availability cascades. With a few horrible exceptions such as 9/11, the number of casualties from terror attacks is very small relative to other causes of death. Even in countries that have been targets of intensive terror campaings, such as Israel, the weekly number of casualties almost never come close to the number of traffic deaths. The difference is in availability of the two risks, the ease and the frequency with which they come to mind. Gruesome images, endlessly repeated in the media, cause everyone to be on edge.

Confirmatory bias

Cognitive scientists have studied our natural tendency to look only for corroboration; they call this vulnerability to the corroboration error the confirmation bias. Once your mind is inhabited with a certain view of the world, you will tend to only consider instances proving you to be right.

Conjunction fallacy

The word fallacy is used, in general, when people fail to apply a logical rule that is obviously relevant. Conjunction fallacy which people commit when they judge a conjunction of two events to be more probable than one of the events in a direct comparison. For example, which alternative is more probable? a) Linda is a bank teller. b) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement. Here bank teller and feminist is less probable than probability of her being a bank teller. When you specify a possible event in greater detail you can only lower it’s probability. This is a classic example of when logic is competing against representativeness, the representativeness wins. More people confuse the probability of two events occuring (bank teller and feminist) to be more probable than one of the events (bank teller).

Certainty Effect

In the four examples below, your chances of receiving $1 million improve by 5%. Is the news equally good in each case? A. From 0 to 5% B. From 5 to 10% C. From 60 to 65% D. From 95 to 100%

The improvement from 95% to 100% is qualitative change that has a large impact, the certainty effect. Outcomes that are almost certain are given less weight than their probability justifies.

Imagine that you inherited $1 million, but your greedy stepsister has contested the will in court. The decision is expected tomorrow. Your lawyer assures you that you have a strong case and that you have a 95% chance to win, but he takes pains to remind you that judicial decisions are never perfectly predictable. Now you are approached by a risk-adjustment company, which offers to buy your case for $910,000 outright -take it or leave it. The offer is lower (by $40,000) than the expected value for waiting for the judgement ($950,000), but are you quite sure you would want to reject it? If such an event actually happens in your life, you should know that a large industry of “structured settlements” exists to provide a certainty at hefty price, by taking advantage of the certainty effects.

Contrast-Misreaction Tendency

Because the nervous system of man does not naturally measure in absolute scientific units, it must instead rely on something simpler. The eyes have a solution that limits their programming needs: the contrast in what is seen in registered. And as in sight, so does it go, largely, in the other senses. Morever, as perception goes, so goes cognition. The result is man’s Contrast-Misreaction Tendency.

A bridge-playing pal of Charlie once told him that a frog tossed into very hot water would jump out, but that same frog would end up dying if placed in room temperature water that was later treated at a very slow rate. Many businesses die in just the manner claimed by pal for the frog. Cognition, misled by tiny changes involving low contrast, will often miss a trend that is destiny.

One of the Ben Franklin’s best-remembered and most useful aphorisms is “A small leak will sink great ship.” The utility of the aphorism is large precisely because the brain so often misses the funcitonal equivalent of a small leak in great ship.

Curiosity Tendency

There is a lot of innate curiosity in mammals, but its nonhuman version is highest among apes and monkeys. In advanced human civilization, culture greatly increases the effectiveness of curiosity in advancing knowledge. For instance, Athens developed much math and science out of pure curiosity while Romans made almost no contribution to either math or science. They instead concentrated their attention on the “practical” engineering of mines, roads, aqueducts, etc.

The curious are also provided with much fun and wisdom long after formal education has ended.

Denominator neglect

The idea of denominator nelect helps explain why different ways of communication risks vary so much in their effects. You read that “a vaccine that protects children from a fatal disease carrries a 0.001% risk of permanent disability.” The risk appears small. Now consider another description of the same risk: “One of 100,000 vaccinated children will be permanently disabled.” The second statement does something to your mind that the first does not: it calls up the image of and individual child who is permanently disabled by a vaccine; the 99,999 safely vaccinated children have faded into the background.

As predicted by denominator neglect, low-probability events are much more heavily weighted when described in terms of relative frequencies (how many) than when stated in more abstract terms of “chances,” “risk,” or “probability” (how likely).

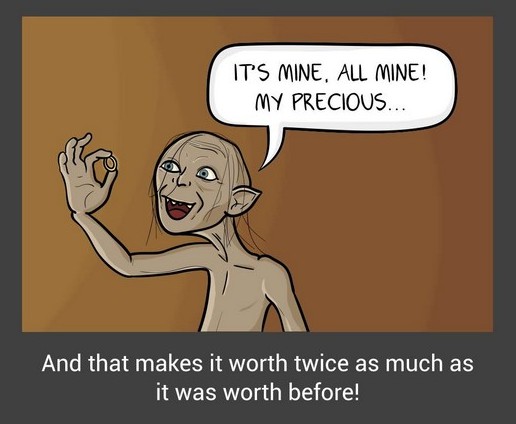

Endowment Effect

Endowment effect is used to describe the relunctance of people to part from assets that belong to their endowment. People tend to overvalue what belongs to them relative to the value they would place on the same possession if it belonged to someone else.

Suppose you hold a ticket to a sold-out concert by a popular band, which you bought at the regular price of $200. You are an avid fan and would have been willing to pay up to $500 for the ticket. Now you have have your ticket and you learn on the Internet that richer or more desperate fans are offering $3,000. Would you sell?

If you resemble most of the audience at sold-out events you do not sell. Your lowest selling price is above $3,000 and your maximum buying price is $500. This is an example of an endowment effect.

Envy/Jealousy Tendency

A memeber of species designed through evolutionary process to want often-scarce food is going to be driven strongly toward getting food when it first sees food. And this is going to occur often and tend to create some conflict when the food is seen in possession of another member of the same species. This is probably the evolutionary origin of the Envy/Jealousy Tendency that lies so deep in human nature.

Envy/Jealousy is so extreme in modern life. For instance, university communities often go bananas when some university employee in money management, or some professor in surgery, gets annual compensation in multiples of the standard professorial salary. And in modern investment banks, law firsm, etc, the envy/jealousy effects are usually more extreme than they are in university faculties. Many big law firms, fearing disorder from envy/jealousy, have long treated all senior partners alike in compensation, no matter how different their contributions to firm welfare. To this Charlie often quotes, “It is not greed that drives the world, but envy.”

Epistemic Arrogance

Epistemic Arrogance refers to our hubris concerning limitation of our knowledge. Epistēmē is a Greek word that refers to knowledge. True, our knowledge does grow, but it is threatened by greater increases in confidence, which make our increase in knowledge at the same time an increase in confusion, ignorance, and conceit. Epistemic Arrogance measures the difference between what someone actually knows and how much he thinks he knows.

Excessive Self-Regard Tendency

We all commonly observe the excessive self-regard of man. He mostly misappraises himself on the high side, like the 99% of Swedish drivers that judge themselves to be above average. Such misappraisals also apply to a person’s major “possessions.” One spouse usually overappraises the other spouse. And a man’s children are like wise appraised higher by him than they are likely to be in a more objective view. Man’s excess of self-reggard typically makes him strongly prefer people like himself.

There is a famous passage somewhere in Tolstoy that illuminates the power of Excessive Self-Regard Tendency. According to Tolstoy, the worst criminals don’t appraise themselves as all that bad. They come to believe either (1) that they didn’t commit their crimes or (2) that, considering the pressures and disadvantages of their lives, it is understandable and forgivable that they behaved as they did and became what they became.

Deprival Superreaction Tendency / Loss Aversion

The quantity of man’s pleasure from a ten dollar gain does not exactly match the quantity of his displeasure from a ten-dollar loss. That is, loss seems to hurt more than the gain seems to help. Morever, if a man almost gets something he greatly wants and has it jerked away from him at the last moment, he will react much as if he had long owned the reward and had it jerked away. This loss of possessed reward and the loss of almost-possessed reward is called Deprival Superreaction Tendency.

A man ordinarily reacts with irrational intensity to even a small loss, or threatened loss, of property, love, friendship, dominated territory, opportunity: status, or any other value thing. As a natural result, bureaucratic infighting over the threatened loss of dominated territory often causes immense damage to an institution as a whole. Deprival Superreaction Tendency is also a huge contributor to ruin from compulsion to gamble. First, it causes the gambler to have a passion to get even once he has suffered loss, and the passion grows with the loss. Second, the most addivtive forms of gambling provide a lot of near missed and each one triggers Deprival Superreaction Tendency.

Disliking/Hating Tendency

In a pattern obverse to Liking/Loving Tendency, the newly arrived human is also “born to dislike and hate” as triggered by normal and abnormal triggering forces in its life. It is the same with most apes and monkeys.

At family level we often see one sibling hate his other siblings and litigate with them endlessly if he can afford it. Indeed Warren Buffett has repeatedly explained to Charlie that “a major difference between rich and poor people is that the rich people can spend their lives suing their relatives.”

Doubt-Avoidance Tendency

The brain of man is programmed with a tendency to quickly remove doubt by reaching some decision. It is easy to see how evolution would make animals, over the eons, drift toward such quick elimination of doubt. After all, the one thing that is surely counterproductive for a prey animal that is threatened by a predator is to take a long time in deciding what to do. And so man’s Doubt Avoidance Tendency is quite consistent with the history of his ancient, nonhuman ancestors.

We shall see later when we get to Social-Proof Tendency and Stress-Influence Tendency, what usually triggers Doubt-Avoidance Tendency is some combination of puzzlement and stress.

First conclusion bias

Keynes reported that human mind works a lot like the human egg, when one sperm gets into a human egg, there’s an automatic shut-off device that bars any other sperm from getting in. The human mind tends strongly towards the same sort of result. And so, people tend to accumulate large mental holdings of fixed conclusions and attutudes that are note often reexamined or changed, even though there is plenty good evidence that they are wrong.

One of the most successful users of an antidote to first conclusion bias was Charles Darwin. He trained himself, early, to intensively consider any evidence tending to disconfirm any hypothesis of his, more so if he thought his hypothesis was a particularly good one. The opposite of what Darwin did is now called confirmation bias.

Future blindness

Austistic people cannot put themselves in the shoes of others, cannot view the world from their standpoint. They cannot perform simple mental operations as “he knows that I don’t know that I know,” and it is this inability that impedes their social skills. Just as autism is called “mind blindness”, this inability to think dynamically, to position oneself with respect to a future observer, we call it “Future blindness.”

Gambler’s fallacy

People expect that the essential charcteristics of the process will be represented, not only globally in the entire sequence, but also locally in each of its parts. In considering tosses of a coin for heads or tails, for example, people regard the sequence H-T-H-T-T-H to be more likely than the sequence H-H-H-T-T-T which does not appear random, also more likely than the sequence H-H-H-H-T-H, which does not represent fairness of coin.

After observing a long run of red on the roulette wheel, for exaple, most people erroneously believe that black is noe due, presumably because the occurence of black will result in more representative sequence than the occurence of an additional red.

Halo Effect

The tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person including things you have not observed is known as the halo effect.

You met a woman named Joan at a party and find her personable and easy to talk to. Now her name comes up as someone who could be asked to contribute to a charity. What do you know about Joan’s generosity? The correct answer is that you know virtually nothing, because there is little reason to believe that people who are agreeable in social situations are also generous contributors to charities. But you like Joan and you will retrieve the feeling of liking her when you think of her. You also like generous people and generosity. By association, you are predisposed to believe that Joan is generous. And now that you believe she is generous, you probably like Joan even better than you did earlier, becaise you have added generosity to her pleasant attributes. Real evidence of generosity is missing in the story of Joan, and the gap is filled by a guess that fits one’s emotional response to her.

Hedonic Treadmill

The hedonic treadmill, also known as hedonic adaptation, is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes. According to this theory, as a person makes more money, expectations and desires rise in tandem, which results in no permanent gain in happiness.

Hindsight bias

Also know as “I-knew-it-all-along” effect.

The worse the consequence, the greater the hindsight bias. In the case of a catastrophe, such as 9/11, we are especially ready to believe that the officials who failed to anticipate it were negligent or blind. On July 10, 2001, CIA obtained information that al-Qaeda might be planning a major attack against US. When the facts later emerged, Ben Bradlee, legendary executive of The Washington Post, declared, “It seems to me elementary that if you’ve got the story that’s going to dominate history you might as well go right to the president.” But on July 10, no one knew - or could have known 0 that this tidbit of intelligence would turn out to dominate history.

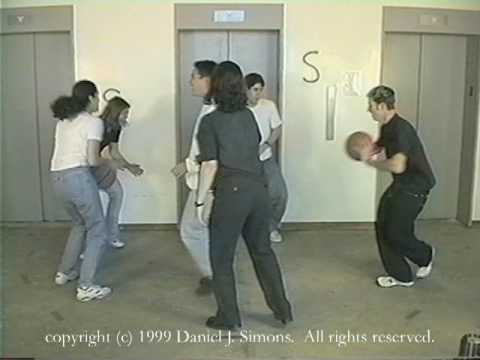

Inattention Blindness Bias

Intense focusing on a task can make people effectively blind, even to the stimuli that normally attract attention.

The following video demonstration was offered by Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons. They constructed a short film of two teams passing basketballs, one team wearing white shirts, the other wearing black. The viewers of the film are instructed to count the number of passes made by the white team, ignoring the black players. This task is difficult and completely absorbing.

Halfway through the video, a woman wearing a gorilla suit appears, crosses the court, thumps her chest, and moves on. The gorilla is in view for 9 seconds. Many thousands of people have seen the video, and about half of them do not notice anything unusual. It is the counting task - and especially the instruction to ignore one of the teams - that casuses the blindness.

The gorilla study illustrates two important facts about our minds: we can be blind to the obvious, and we are also blind to our blindness.

Incentive-caused bias

Charlie advices that we should heed the general lesson implicit in the injuction of Ben Franklin in Poor Richard’s Almanack: “If you would persuade, appeal to interest and not to reason.” This maxim is a wise guide to a great and simple precaution in life: Never, ever think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives. Charlie once saw a very smart house counsel for a major investment bank lose his job, with no moral fault, because he ignored the lesson in this maxim of Franklin. This counsel failed to persuade his client because he told him his moral duty, as correctly conceived by the counsel, without also telling the client in vivid terms that he was very likely to be clobbered to smithereens if he didn’t behave as his counsel recommended. As a result, both client and counsel lost their careers.

How much sugar is in a Coca- Cola supersize cup? In the video below, BBC Newsnight’s Jeremy Paxman asks the same question to James Quincey, president of Coca Cola Europe.

Whose bread I eat, his song I sing. The inevitable ubiquity of incentive-caused bias has vast, generalized consequences. For instance, a sales force living only on commissions will be much harder to keep moral than one under less pressure from the compensation arrangement. On the other hand, a purely commissioned sales force may well be more efficient per dollar spent. Therefore, difficult decisions involving trade-offs are common in creating compensation arrangements in the sales function.

Inconsistency-Avoidance Tendency

The brain of man conserves programming space by being reluctant to change, which is a form of inconsistency avoidance. We see this in all human habits, constructive and destructive. Few people can list a lot of bad habits that they have eliminated, and some people cannot identify even one of these. Instead, practically everyone has a great many bad habits he has long maintained despite their being known as bad.

So great is the bad-decision problem caused by Inconsistency-Avoidance Tendency that our courts have adopted important strategies against it. For instance, before making decisions, judges and juries are required to hear long and skillful presentation of evidence and argument from the side they will not naturally favor, given their ideas in place. And this helps prevent considerable bad thinking from “first conclusion bias.” Similarly, other modern decision makers will often force groups to consider skillful counterarguments before making decisions.

Influence-from-Mere Association

Consider the case of many men who have been trained by their previous experience in life to believe that when several similar items are presented for purchase the one with the highest price will have the highest quality. Knowing this, some seller of an industrial product will often change his product’s trade dress and raise its price significantly hoping that quality-seeking buyers will be tricked into becoming purchasers by mere association of his product and its high price.

Even association that appears to be trivial, if carefully planned, can have extreme and peculiar effects on purchasers of the product. Adcertisers know about the power of mere association. You won’t see Coke advertised alongside some account of the death of a child. Instead, Coke ads picture life as happier than reality. A common bad effect from the mere association of a person and a hated outcome is dispayed in “Persian Messenger Syndrome.” Ancient Persians actually killed some messengers whose sole fault was that they brought home truthful bad news, say, of a battle lost. It was actually safer for the messenger to run away and hide, instead of doing his job as a wiser boss would have wanted it done.

Intensity Matching

Questions about your happiness, the president’s popularity, the proper punishment of financial evildoers, and the future prospects of a politician share an important characteristic: they all refer to an underlying dimension of intensity or amount, which permits the use of the word more: more happy, more popular, more severe, or more powerful(for a politician).

For example, the question of How much would you contribute to save an endangered species? is replaced by How much emotion do I feel when I think of dying dolphins? The feelings about dying dolphins is expressed in dollars. Intensity matching is available to solve that problem. Both feelings and contribution dollars are intensity scales. I can feel more or less strongly about dolphins and there is a contribution that matches the intensity of my feelings. The dollar amount that will come to my mind is the matching amount.

Illusion of Pundits or Expert Problem

Philip Tetlock, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania, explored so-called expert predictions in a landmark twenty-year study, which he published in his book Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?. In an experiment consisting of 284 people who made their living “commenting or offering advice on political and economic trends”, Tetlock asked themto assess their probabilities that certain events would occur in the not too distant future, both in areas of the world in which they specialized and in regions about which they had less knowledge.

The results were devastating. The experts performed worse than they would have if they had simply assigned equal probabilities to each of the 3 possible outcomes. The person who acquires more knowledge develops an enhanced illusion of their skill and becomes unrealistically overconfident. The experts resisted admitting that they had been wrong, and when they were compelled to admit error, they had a large collection of excuses. Experts are human in the end. They are dazzled by their own brilliance and hate to be wrong. Experts are led astray not by what they believe, but by how they think, says Tetlock.

He uses the terminology from Isaiah Berlin’s essay on Tolstoy, “The Hedgehog and the Fox”. Hedgehogs “know one big thing” and have a theory about the world; they account for particular events within a coherent framework, bristle with impatience toward those who don’t see things their way and are confident in their forecasts. Foxes, by contrast, are complex thinkers. They don’t believe that one big thing drives the march of history. Instead the foxes recognize that reality emerges from the interactions of many different agents and forces, including blind luck, often producing large and unpredictable outcomes.

Illusion of Skill

A major industry appears to be built largely on an illusion of skill. The diagnostic for the existence of any skill is the consistency of individual differences in achievement. The logic is simple: if individual differences in any one year are due entirely to luck, the ranking of investors and funds will vary erratically and the year-to-year correalation will be zero. When there is skill, however, the rankings will be more stable. The persistence of individual difference is the measure by which we confirm the existence of skill among golfers, car salespeople, orthodontists, or speedy toll collectors on the turnpike.

Law of Small Numbers

People are not adequately sensitive to the sample size.

In a telephone poll of 300 seniors, 60% support the president.

If you had to summarize this message in exactly 3 words, it almost certainly would be “elderly support president”. The omitted details of the poll, that it was done on the phone with a sample of 300, are of no interest in themselves. Your summary would be same if the sample size would be different. The exaggerated faith of researchers in what can be learned from a few observations is closely related to halo effect, the sense we often get that we know and understand a person about whom we actually know very little.

A well known example of this is the supposed ‘Mozart effect’. A study suggested that playing classical music to babies and young children might make them smarter. The findings spawned a whole cottage industry of books, CD and videos. The study by psychologist Frances Rauscher was based upon observations of just 36 college students. In just one test students who had listened to Mozart “seemed” to show a significant improvement in their performance in an IQ test. This was picked up by the media and various organizations involved in promoting music. However, in 2007 a review of relevant studies by the Ministry of Education and Research in Germany concluded that the phenomenon was “nonexistent”.

Liking/Loving Tendency

Liking or loving, interwined with admiration in a feedback mode, often has vast practical consequences in areas far removed from sexual attachments. Fot instance, a man who is so constructed that he loves admirable persons and ideas with a special intensity has a huge advantage in life. This blessing came to both Buffett and Charlie in large measure, sometimes from the same persons and ideas.

Linda Problem

Which alternative is more probable?

a) Linda is a bank teller. b) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Experimenting extended version of this questionnaire found that 89% of undergraduates in sample violated the logic of probability. The same questionnaire with doctoral students in decision-science program of Stanford Graduate Scholl of Business, all of whom had taken several advanced courses in probability, statistics and decision theory, 89% of these respondents ranked “feminist bank teller” as more likely than “bank teller”. About 85% to 90% of undergraduates at several major universities chose the second option, contrary to logic.

Lets consider the judgements of likelihood of two scenarios. Think in terms of Venn diagrams. The set of feminist bank tellers is wholly included in the set of bank tellers. as every feminist bank teller is a bank teller. Therefore the probability othat Linda is a feminist bank teller must be lower than the probability of her being a bank teller.

Ludic fallacy

Ludic comes from ludus, Latin for games. The attributes of the uncertainty we face in real life have little connection to the sterilized ones we encounter in exames and games.

Mental Model Fallacy

Using the example from this blog on mental model fallacy, suppose one day you decide that you want to be MMA champion. So, off you spending all time listening to MMA commentators as they describe the secrets of how MMA superstars win. But where only listening commentators and MMA fighters is not good enough if you don’t practice. If you lack practice, then you will lack the necessary mental architecture to understand the knowledge they possess. As concluded in the blog, “Therefore, without practice, and without ascending the skill tree that these MMA champions inhabit, you are unlikely to understand the insights that they have to offer. And worse, if you are listening to non-practitioners parroting what they’ve heard from the fighters themselves, you are adding a layer of indirection over something that is already difficult to communicate.” As it is for MMA fighters, so it is for business, software engineering, investing, decision making, and life.

Naïve empiricism

We have a natural tendency to look for instances that confirm our story and our vision of the world -these instances are always easy to find. Alas, with tools, and fools, anything can be be easy to find.

Narrative fallacy

Naravtive fallacy are used to describe how flawed stories of the past shape our views of the world and our expectations for the future. Taleb suggests that we humans constantly fool ourselves by constructing filmsy accounts of the past and believing they are true.

Omission neglect

When we fail to think about what we do not know, we underestimate the importance of missing information, and this leads us to form strong opinions even when the available evidence is weak. This can lead to bad decisions that we later regret.

Overoptimism Tendency

About three centuries before the birth of Christ, Demosthenes, the most famous Greek orator, said, “What a man wishes, that also will he believe.” The Greek orator was clearly right about an excess optimism being the normal human condition, even when pain or threat of pain is absent. Witness happy people buying lottery tickets.

Outcome bias

We are prone to blame decision makers for good decisions that worked out badly and to give them too little credit for successful moves that appear obvious only after the fact. There is a clear outcome bias. When the outcomes are bad, the clients often blame their agents for not seeing the handwriting on the wall - forgetting that it was written in invisible ink that became legible only afterwards.

Planning fallacy

Overly optimistic forecasts of the outcome of projects are found everywhere. Examples of planning fallacy abound in the experiences of individuals, governments, and businesses. The list of horror stories is endless.

In July 1997, the proposed new Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh was estimated to cost up to £40 million. By June 1999, budget for building was £109 million. In April 2000, legislators imposed a £195 million “caps on costs.” By November 2001, they demanded an estimate of “final cost,” which was set at £241 million. That estimated finak cost rose twice in 2002, ending the year at £294.6 million. It rose three times more in 2003, reaching £375.8 million by June. The building was finally completed in 2004 at an ultimate cost of roughly £431 million.

Possibility Effect

In the four examples below, your chances of receiving $1 million improve by 5%. Is the news equally good in each case? A. From 0 to 5% B. From 5 to 10% C. From 60 to 65% D. From 95 to 100%

Increasing the chances from 0 to 5% transforms the situation, creating a possibility that did not exist earlier, a hope of winning the prize. It is a qualitative change. Ther large impact of 0 to 5% illustrates the possibility effect.

Possibility effect causes highly unlikely outcomes to be weighted disproportionately more than they “deserve”. People who buy a lottery tickets in vast amounts show themselves willing to pay much more than expected value for very small chance to win a large prize.

When a loved one is wheeled into surgery, a 5% risk that an amputation will be necessary is very bad -much more than half as bad as a 10% risk. Because of the possiblity effect, we tend to overweight small risks and are willing to pay far more than expected value to eliminate them altogether.

Reciprocation Tendency

The automatic tendency of humans to reciprocate both favors and disfavors, has long been noticed as it is in apes, monkeys, dogs and many less cognitively gifted animals. We see extreme power of tendency to reciprocate disfavors in some wars, wherein it increases hatred to a level causing very brutal conduct. For long stretches in many wars, no prisoners were taken; the only acceptable enemy is a dead one. And sometimes that was not enough, as in the case of Genghis Khan, who was not satisfied with corpses. He insisted on their being hacked to pieces.

And the very best part of human life probably lies in relationships of affection wherein parties are more interested in pleasing tha being pleased – a not uncommon outcome in display to reciprocate favor tendency.

Regression to the mean

Highly intelligent women tend to marry men who are less intelligent than they are.

You can get a good conversation started at a party by asking for a explaination. Some may think of highly intelligent women wanting to avoid the competition of equally intelligent men, or being forced to compromise in thier choice of spouse because intelligent men do not want to compete with intelligent women.

Consider this statement: The correlation between the intelligence scores of spouses is less than perfect. This statement is obviously true and not interesting at all. If the correlation between the intelligence of spouses is less than perfect (and if men and women onaverage do not differ in intelligence) then it is a mathematical inevitability that highly intelligent women will be married to husbands who are on average less intelligent than they are. The observed regression to the mean cannot be more interesting or more explainable than the imperfect correlation.

Our mind is strongly biased toward causal explanationsand does not deal well with “mere statistics.” When our attention is called to an event, associative memory will look for its cause -more preciselyl activation will automatically spread to any cause that it already stored in memory. Causal explainations will be evoked when regression is detected, but they will be wrong because the truth is that regression to the mean has an explaination but does not have a cause. The event that attracts our attention in golfing tournament is the frequent deterioration of the performance of the golfers who were successful on day 1. The best explaination of it is that those golfers were unusually lucky that day but this explaination lacks the causal force that our minds prefer.

Representativeness

One sin of representativeness is an excessive willingness to predict the occurence of unlikely events. Representativeness belongs to a cluster of closely related basic assessments that are likely to be generated together.

Here is an example : you see a person reading The New York Times on the New York subway. Which of the following is better bet about the reading stranger? She has a PhD or She does not have a college degree.

The most representative outcomes combine with the personality description to produce the most coherent stories. The most coherent stories are not necessarily the most probable, but they are plausible, and the notions of coherence, plausibility, and probability are easily confused by the unwary.

Selection Bias

In Littlewood’s Law and the Global Media, Gwern Branwen explains that selection effects in media become increasingly strong as populations and media increase, meaning that rare datapoints driven by unusual processes such as the mentally ill or hoaxers are increasingly unreliable as evidence of anything at all and must be ignored. At scale, anything that can happen will happen a small but nonzero times.

Describing the news or media as having a “selection bias problem” is a bit odd, and like describing bombs as having a mortality problem; arguably, the sole function of the news is to be a giant global selection bias.

Social-Proof Tendency

The otherwise complex behavior of man is much simplified when he automatically thinks and does what he observes to be thought and done around him. And such followership often works fine. For instance, what simpler way could there be to find out how to walk a big football game in a strange city than by following the flow of the crowd. For some such reason, man’s evolution left him with Social-Proof Tendency.

And in highest reaches of bussiness, it is not all uncommon to find leaders who display followership akin to that of teenagers. If one oil company foolishly buys a mine, other oil companies often quickly join in buying mines. So also if the purchased company makes fertilizer. Both of these oil company buying fads actually bloomed, with bad results.

In social proof, it is not only action by others that misleads but also their inaction. In the presence of doubt, inaction by others becomes social proof that inaction is the right course. Thus, the inaction of a great many bystanders led to the death of Kitty Genovese in a famous incident much discussed in introductory pyschology courses.

If only one lesson is to be chosen from a package of lesson involving Social-Proof Tendency, and used in self improvement, Charlie’s favorite would be: Learn how to ignore the examples from others when they are wrong, because few skills are more worth having.

Stress-Influence Tendency

Everyone recognizes that sudden stress, for instance from a threat, will cause a rush of adrenaline in the human body, prompting faster and more extreme reaction. And everyone who has taken Psych 101 knows that stress makes Social-Proof Tendency more powerful.

In a phenomenon less well recognized, but still widely known, light stress can slightly improve performance – say, in examinations -whereas heavy stress causes dysfunction.

Substitution

Substituting one question for another can be a good strategy for solving difficult problems. Geroge Pólya included subsitution in his classic How to Solve It: “If you can’t solve a problem, then there is an easier problem you can solve: find it.”

Sunk-cost fallacy

The decision to invest additional resources in a losing account, when better investments are available, is known as sunk-cost fallacy, a costly mistake that is observed in decisions large and small. Driving into the blizzard because one paid for tickets is a sunk-cost error. The sunk-cost fallacy keeps people for too long in poor jobs, unhappy marriages, and unpromising research projects.

Imagine a company that has already spent $50 million on a project. The project is now behind schedule and the forecasts of it ultimate returns are less favorable than at the initial plaaning stage. An additional investmentof $60 million is required to give the project a chance. An alternative proposal is to invest the same amount in a new project that currently looks likely to bring higher returns. What will company do? All too often a company afflicted by sunk costs drives into the blizzard, throwing good money after bad rather than accepting the humiliation of closing the account of a costly failure.

Theory-induced blindness

Once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws. If you come upon an observation that does not seem to fit the model, you assume that there must be a perfectly good explaination that you are somehow missing. You give theory the benefit of the doubt, trusting the community of experts who have accepted it.

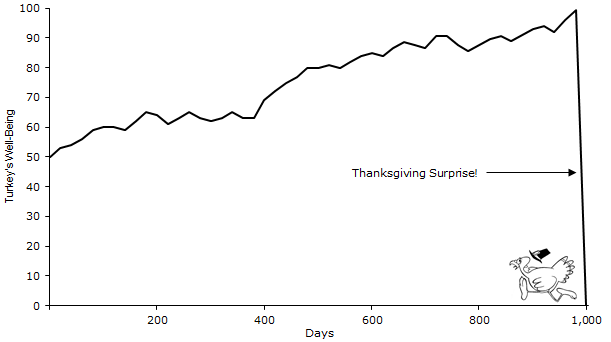

Turkey Problem or Riddle of Induction

Consider a turkey that is fed every day. Every single feeding will firm up the bird’s belief that it is the general rule of life to be fed every day by friendly members of the human race. On the afternoon of the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, something unexpected will happen to the turkey, It will incur a revision of belief.

Something that has worked in the past, until -well, it unexpectedly no longer does, and what we have learned from the past turns out to be at best irrelevant or false, at worst viciously misleading. You subsequently derive solely from past data a few conclusions concerning the properties of pattern with projections for the next thousand, even five thousand, days, On the one thousand and first day – boom!

WYSIATI

What You See Is All There Is. WYSIATI facilitates the achievement of coherence and of the cognitive ease that causes us to accept a statement is true. It explains why we can think fast, and how we are able to make sense of partial information in a complex world. Much of the time, the coherent story we put together is close enough to reality to support reasonable action.

Consider the following : “Will Mindik be a good leader? She is intelligent and strong…” An answer quickly came to your mind, and it was yes. You picked the best answer based on the very limited information available, but you jumped the gun. What if the next two adjectives were corrput and cruel?

That’s a lot to digest. What should I do with all this? Use it to enhance your vocabulary or just try to catch one of these and become a better human by avoiding it. It’s not an easy game, but a fun way for self improvement.

Do you want to see how Charlie applies this to a real world example? The example involves McDonnell Doglas airliner evacuation test.

Before a new airliner can be sold, the government requires that it pass an evacuation test, during which a full load of passengers must get out in some short period of time. The government directs that the test be realistic. So you can’t pass by evacuating only twenty-year-old athletes. So McDonnell Douglas scheduled such a test in a darkened hangar using a lot of old people as evacuees. The passenger cabin was, say, twenty feet above concrete floor of the hangar and was to be evacuated through moderately flimsy rubber chutes. The first test was made in the morning. There were about twenty very serious injuries, and the evacuation took so long it flunked the time test. So what did McDonnell Douglas next do? It repeated the test in the afternoon, and this time there was another failure, with about twenty more serious injuries, including one case of permanent paralysis.

What pyschological tendencies contributed to these terrible results? Charlie using his checklist of tendencies, comes up with following explaination. Reward-Superresponse Tendency drove McDonnell Douglas to act fast. It couldn’t sell its airliner until it passed the test. Also pusing the company was Dobut-Avoidance Tendency with its natural drive to arrive at a decision and run with it. The the government’s direction that test be realistic drove Authority-Misinfluence Tendency into the mischief of causing McDonnell Douglas to overreact by using what was obviusly too dangerous a test method. By now the course of action had been decided, so Inconsistency-Avoidance Tendency helped preserve the near idiotic plan. When all the old people got to the dark hangar, with its high airline cabin and concrete floor, the situation must have made McDonnell Douglas employees and supervisors not objecting. Social-Proof Tendency, therefore, swamped the queasiness. And this allowed continued action as planned, a continuation that was aided by more Authority-Overinfluence Tendency. Then cam the disaster of the morning test with its failure, plus serious injuries. McDonnell Douglas ignored the strong disconfirming evidence from the failure of first test because confirmation bias, aided by the trigeering of strong Deprival Superreaction Tendency favored maintaining the original plan. McDonnell Douglas’ Deprival Superreaction Tendency was now like that which causes a gambler, bent on getting even after a huge loss, to make his final big bet. After all McDonnell Douglas was going to lose a lot if it didn’t pass its test as scheduled.

Happy Learning!

Credits

NOTE

Questions, comments, other feedback? E-mail the author