Introduction

The first part of this series of blog introduces the problem for human-like intelligence.

The authors of the paper “Building machines that learn and think like people” propose 3 core ingredients needed for human-like learning and thought. Authors believe that integrating them will produce significantly more powerful and more human-like learning and thinking abilities than we currently see in AI systems.

In second post, we will go through each of the ingredients proposed by the authors and see how each of these ingredients helps in solving the two challenges of Character Challenge and Frostbite Challenge.

The 3 core ingredients are:

3 Core Ingredients

1. Developmental start-up software

In TED Talk by Alison Gopnik on “What do babies think?”, If you’d asked people this 30 years ago, most people, including psychologists, would have said that this baby was irrational, illogical, egocentric – that he couldn’t take the perspective of another person or understand the cause and effect. In last 20 years, developmental science has completely overturned that picture. So, in some ways, we think that this baby’s thinking is like the thinking of the most brilliant scientists.”

Guess, What am I thinking?

Babies and young children are like scientists. Scientists do stastical analysis while babies and young children do experiements and draw conclusions. Grown-ups think in terms of a goal — planning, acting and doing to make things happen or accomplish the goal. Babies don’t have that narrow, goal-directed approach to the world. They’re open to all the information that will tell them something new.

The “child as scientist” proposal further views the process of learning itself as also scientist-like, with recent experiments showing the children seek out data to distinguish between hypothese, isolate variables, test causal hypotheses, make use of the data-generating process in drawing conclusions, and learn selectively from others.

One such study done by Fei Xu at University of California, Berkeley1, shows how even babies can understand the relation between a statistical sample and a population. 8-month old babies were shown box full of mixed ping-pong balls: for instance, 80% white and 20% red. The experimenter would then take out 5 balls, at random. The babies were more surprised (that is, looked longer and more intently at the scene) when the experimenter pulled four red balls and one white one out of the box – an improbable outcome – than when she pulled out four white balls and one red one.

1.1 Intuitive physics

Researchers such as Renée Baillargeon of the University of Illinois and Elizabeth S. Spelke of Harvard University1 found that infants understand fundamental physical relations such as movement trajectories, gravity and containment. They look longer at a toy car appearing to pass through a solid wall than at events that fit basic principles of everyday physics. By the time they are three or four, children have elementary ideas about biology and a first understanding of growth, inheritance and illness. This early biological understanding reveals that children go beyond superficial perceptual appearances when they reason about objects.

Ahhhhh....

What are the prospects for embedding or acquiring this kind of intuitive physics in deep learning systems?

A paper from FAIR, PhysNet shows an exiciting step in this direction. PhysNet trains a deep convnet to predict the stability of block towers from simulated images of two, three and foir cubical blocks stacked vertically. Result is, PhysNet impressively generalizes to simple real images of block towers, matching human performance on these images, also exceeding human performance on synthetic images. Problem is, PhysNet requires extensive training - between 10,000 to 20,000 scenes - to learn judgments for single task (will tower fall?). In contraty, people require far less experience to perform any particular task, and can generalize to many variations in the scene with no retraining required. Now, question is Could PhysNet capture this flexibility, without explicitly simulating the causal interactions between objects in 3-D?

Could neural networks be trained to emulate a general-purpose physics simulator, given the right type and quantity of training data, such as the raw input experienced by a child?

For deep networks trained on physics-related data, it remains to be seen whether higher layers will encode objects, general physical properties, forces and approximately Newtonian dynamics. Consider for example a network that learns to predict the trajectories of several balls bouncing in a box. If this network has actually learned something like Newtonian mechanics, then it should be able to generalize to interestingly different scenarios – at a minimum different numbers of differently shaped objects, bouncing in boxes of different shapes and sizes and orientations with respect to gravity, not to mention more severe generalization tests.

In the case of our challenges, learning to play Frostbite, incorporating a physics-engine-based representation could help DQNs learn to play games such as Frostbite in a faster and more general way, whether the phyiscs knowledge is capture implicitly in a neural network or more explicity in a simulator. It can also reduce the need of larger datasets and retraining if objects like birds, fish, etc are slightly modified in their behavior, reward structure or apearance. For e.g. when a new object type such as a bear is introduced, in later levels of Frostbite, a network endowed with intuitive physics would also have an easier time adding this object type to its knowledge.

1.2 Intuitive psychology

For babies and young children, the most important knowledge of all is knowledge of other people. In one experiment1, an experimenter showed 14- and 18-month-olds a bowl of raw broccoli and a bowl of goldfish crackers and then tasted some of each, making either a disgusted face or a happy face. Then she put her hand out and asked, “Could you give me some?” The 18-month-olds gave her broccoli when she acted as if she liked it, even though they would not choose it for themselves. (The 14-month-olds always gave her crackers.) So even at this very young age, children are not completely egocentric — they can take the perspective of another person, at least in a simple way. By age four, their understanding of every day psychology is even more refined. They can explain, for instance, if a person is acting oddly because he believes something that is not true.

Consider, for example, a scenario in which an agent A (with some books to place in the cabinet) is moving towards the cabinet, an agent B and the cabinet’s door is closed, the infants and adults may interpret this behaviour as “hindering” as the closed door that comes in way of agent A in completing the task or goal(placing books in cabinet). Now the infant interprets the intention of agent A’s act of repetitive bumping into the door and helps the agent A in completing the task.

Could neural networks be trained to provide full formal account of intuitive psychological reasoning, given the right type and quantity of training data?

Similar to the intuitive physics domain, it is possible that with a tremendous number of training trajectories in a variety of scenarios, deep learning techniques could approximate the reasoning found in infancy even without learning anything about goal-directed or social-directed behavior more generally. But this is also unlikely to resemble how humans learn, understand, and apply intuitive psychology unless the concepts are genuine. In the same way that altering the setting of a scene or the target of inference in a physics-related task may be difficult to generalize without an understanding of objects, altering the setting of an agent or their goals and beliefs is difficult to reason about without understanding intuitive psychology.

In our challenge of playing Frostbite, we learned how people can learn to play quickly by watching an experienced player play for just a few minutes. Here, intuitive pyschology lets us infer the beliefs, desires, and intentions of the experienced player. For e.g. player can learn that birds are to be avioded from seeing how the experienced player appears to avoid them.

2. Learning as rapid model building

Even with just a few examples, people can learn remarkably rich conceptual models. One indicator of richness is the variety of functions that these models support. Beyond classification, concepts support prediction, action, communication, imagination, explaination and composition. These abilities are not independent; rather they hand together and interact, coming free with the acquisition of the underlying concept. Children (and adults) have a great capacity for ‘one-shot’ learning – a few examples of a hairbrush, pineapple, or lightsaber and a child understands the category, “grasping the boundary of the infinite set that defines each concept from the infinite set of all possible objects.” On the contrary, neural networks are notoriously data hungry. This suggests that the algorithms underlying neural networks are using the information less efficiently than a person learning to perform similar tasks.

What additional ingredients may be needed in order to rapidly learn more powerful and more general-purpose representations?

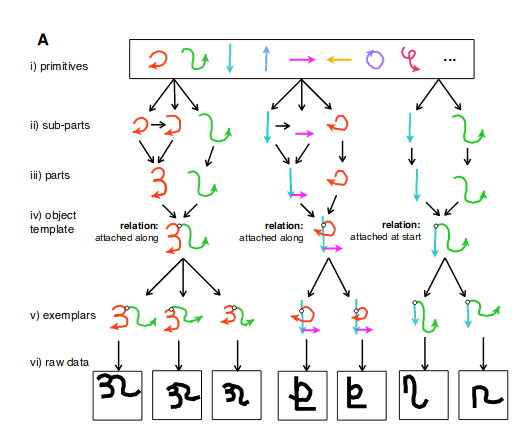

The authors of this paper developed an algorithm using Bayesian Program Learning (BPL) that represents concepts as simple stochastic programs – structured procedures that generate new example of a concept when executed. These programs allow the model to express causal knowledge about how the raw data are formed, and the probabilistic semantics allow the model to handle noise and perform creative tasks. Structure sharing across concepts is accomplished by the compositional reuse of stochastic primitives that can combine in new ways to create new concepts. Here, describing learning as “rapid model building” refers to the fact that BPL constructs generative models (lower-level programs) that produce tokens of a concept.

Learning models of this form allows BPL to perform a challenging one-shot classification task at human level performance and to outperform current deep learning models such as convolutional networks.

2.1 Compositionality

Compositionality is the classic idea that new representations can be constructed through the combination of primitive elements. Compositionality is also at the core of productivity: an infinite number of representations can be constructed from a finite set of primitives, just as the mind can think an infinite number of thoughts, utter or understand an infinite number of sentences, or learn new concepts from a seemingly infinite space of possibilities.

Deep neural networks have at least a limited notion of compositionality.

In our Character challenge, handwritten characters are inherently compositional, where the parts are pen strokes and relations describe how these strokes connect to each other. BPL modeled these parts using an additional layer of compositionality, where parts are complex movements created from simpler sub-part movements. New characters can be constructed by combining parts, sub-parts, and relations in novel ways.

In another challenge of learning to play Frostbite, a scene in the game is composition of various object types, including birds, fish, bear, igloo, ice floes, etc. Many repetitions of the same objects are present at different locations in the scene, and thus representing each as an identical instance of the same object with the same properties is important for efficient representation and quick learning of the game. Further, new levels may contain different numbers and combinations of objects, where a compositional representation of objects – using intuitive physics and intuitive psychology as glue – would aid in making these crucial generalization.

2.2 Causality

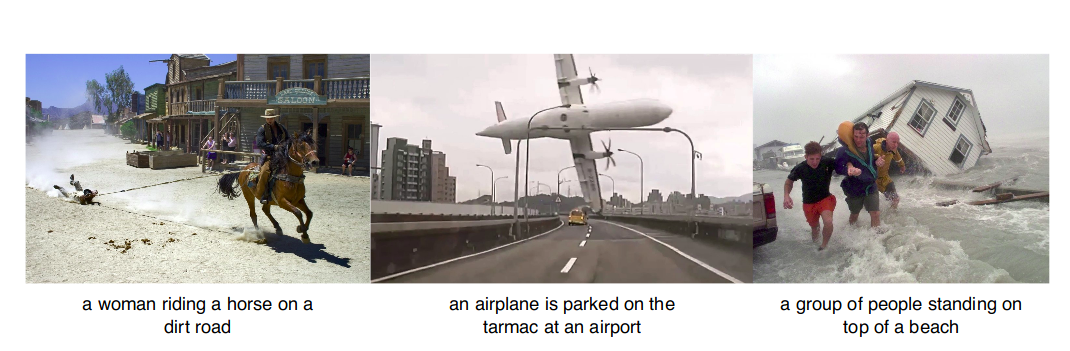

Causal knowledge has been shown to influence how people learn new concepts; providing a learner with different types of causal knowledge changes how they learn and generalize. Beyond concept learning, people also understand scenes by building causal models. Human-level scene understanding involves composing a story that explains the perceptual observations, drawing upon and integrating the ingredients of intuitive physics, intuitive psychology, and compositionality.

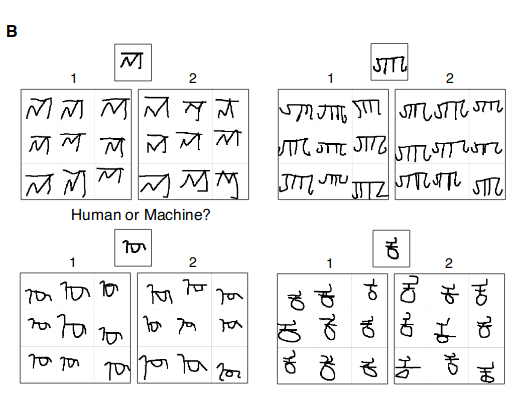

Here, BPL model generates new examples from just one example of a new concept. An example image of a new concept is shown above. One grid was generated by 9 people and the other is 9 samples from the BPL model. Which grid in each pair (A or B) was generated by the machine?2

Here, the network gets the key objects in a scene correct but fails to understand the physical forces at work, the mental states of the people, or the causal relationships between the objects – in other words, it does not build the right causal model of the data. Causality can also glue some features together by relating them to a deeper underlying cause, explaining why some features such as “can fly,” “has wings,” and “has feathers” co-occur across objects while others do not.

In Characters Challenge, the way people learn to write a novel handwritten character influences perception and categorization. By incorporating additional causal, compositional, and hierarchical structure, in sequential generative neural networks, the network could lead to a more computationally efficient and neurally grounded variant of the BPL model of handwritten character.

A causal model of Frostbite would have to be more complex, gluing together object representations and explaining their interactions with intuitive physics and intuitive psychology, much like the game engine that generates the game dynamics and ultimately the frames of pixel images.

2.3 Learning to learn

Learning-to-learn is closely related to the machine learning notions of “transfer learning”, “multi-task learning” or “representation learning.” These terms refer to ways that learning a new task (or a new concept) can be accelerated through previous or parallel learning of other related tasks (or other related concepts).

A champion Jeopardy program cannot hold a conversation, and an expert helicopter controller for aerobatics cannot navigate in new, simple situations such as locating, navigating to, and hovering over a fire to put it out. In contrast, a human can act and adapt intelligently to a wide variety of new, unseen situations. How can we enable our artificial agents to acquire such versatility? In meta learning (learning-to-learn), aim is to build versatile agents that can continually learn a wide variety of tasks throughout their lifetimes.

If deep neural networks could adopt compositional, hierarchical, and causal representations, we expect they might benefit more from learning-to-learn.

In Character Challenge, the neural network approach require much more pretraining than people or BPL approach. BPL transfers readily to new concepts because it learns about object parts, sub-parts, and relations, capturing learning about what each concept is like and what concepts are like in general. It is crucial that learning-to-learn occurs at multiple levels of the hierarchical generative process. We cannot be sure how people get to the knowledge they have in this domain, but the authors think this is how it works in BPL, and think in people it might be similar.

In the Frostbite Challenge, people seem to transfer knowledge at multiple levels, from low-level perception to high-level strategy. Most basically, people parse the game environment into objects, types of objects (compositionality) and causal relations between them (causality). People understand that games like this one, has goal (maybe complete the game, look for easter eggs, etc) and based on prior knowledge, complete the goal by interacting with the game environment and with help of these learning achieve the goals. Deep reinforcement learning systems for playing Atari achieved quite a success by transfer learning, but they still have not come close to learning as quickly as humans.

In sum, the interaction between representation and previous experience may be key to building machines that learn as fast as people do.

A deep learning system trained on many video games may not, by itself, be enough to learn new games as quickly as people do. Yet if such a system aims to learn compositionally structured causal models of a each game – built on a foundation of intuitive physics and psychology – it could transfer knowledge more efficiently and thereby learn new games much more quickly.

3. Thinking Fast

Until now we looked at various ways of how we can squeeze the data to extract rich concepts. But to achieve human-like learning abilities, there is another aspect of time taken to obtain the results or prediction (inference). The speed of perception and thought - the amount of time required to understand a scene, think a thought, or choose an action in humans is so quick. So, to build successful human-like machine, we need to have models that rival humans in inference speed.

3.1 Approximate inference in structured models

There are two contrasting methods, Hirearhical Bayesian models programs over probablistic programs which have model with theory-like structures and rich causal representation of the world but face a challenge in ways for efficient inference, on other hand, deep learning methods have less of causal models and intuitive theories but thanks to Moore’s Law (or Huang’s Law), they provide efficient inference speeds. We humans have this little brain weighing 3 pounds on average consuming only 20 W to perform all activities.

When hypothesis space is vast, and only a few hypotheses are consistent with the data, how can good models be discovered without exhaustive search?

In Frostbite, while playing people may discover some “Aha!” moments: e.g. they will learn that jumping on ice floes causes them to change the color, that in turn causes an igloo to be constructed piece-by-piece, that birds are reponsible for losing points, and fish gains points. These little fragments of a “Frostbite theory” are assembled to form a causal understanding of the game relatively quickly. Similarly, motor programs can be used to infer how people draw a new character.

3.2 Model-based and model-free reinforcement learning

The DQN used in Atari game solving is a simple form of model-free RL in deep neural networks that allows for fast selection of actions. Model-free learning is however not the whole picture. Considerable evidence suggests that the brain also has a model-based learning system, responsible for building a “cognitive map” of the environment and using it to plan action sequences for more complex tasks.

Model-based planning an essential ingredient of human intelligence, enabling flexible adaptation to new tasks and goals; it is where all of the rich model-building abilities discussed in the previous sections earn their value as guides to action.

A marriage of flexibility and efficiency might be achievable if we use the human reinforcement learning systems as guidance.

In Frostbite Challenge, if we bring various design variants except for reward functions, a competent Frostbite player can easily shift behaviour appropriately, with little or no additional learning, and model-based planning approach in which environment model can be modularly combined with arbitary new reward functions and then deployed immediately for planning can be an effective solution.

Intrinsic motivation also plays an important role in human learning and behavior. While much of the previous discussion assumes the standard view of behavior as seeking to maximize reward and minimize punishment, all externally provided rewards are reinterpreted according to the “internal value” of the agent, which may depend on the current goal and mental state. There may also be an intrinsic drive to reduce uncertainty and construct models of the environment, closely related to learning-to-learn and multi-task learning. Deep reinforcement learning is only just starting to address intrinsically motivated learning

Phew! We explored the core ingredients proposed by author to build human-like machines. We looked at different algorithms and how some satisfy either of the ingredients but not all. The road to building such machines is definitely a hard and challenging one. (remember hard, not impossible!) We looked into how deep learning should tackle various learning tasks with few training data as people need, and also evaluate models on a range of human-like generalizations across multiple tasks.

In next blog on the series, I will go through some of peer commentary and what extra ingredients are required that authors missed out.

Happy Learning!

Footnotes and Credits

Causal, Composition and Image Caption Graphics

NOTE

Questions, comments, other feedback? E-mail the author

-

Answers(by row 1, 2, 1, 1) ↩