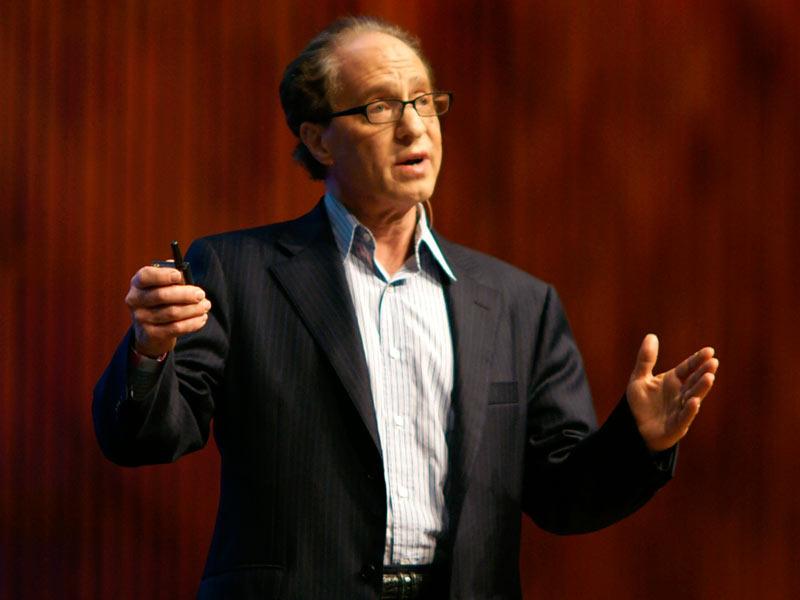

Ray Kurzweil

This a collection of almost everything including stories, lessons, short quotes which I will keep updating often. There is lesson in everything. Happy Learning!

I love the way Ray is introduced by the all hosts everytime, everywhere. I would do the same.

Ray Kurzweil is one of the world’s leading inventors, thinkers, and futurists, with a thirty-year track record of accurate predictions. Called “the restless genius” by The Wall Street Journal and “the ultimate thinking machine” by Forbes magazine, Kurzweil was selected as one of the top entrepreneurs by Inc. magazine, which described him as the “rightful heir to Thomas Edison.” PBS selected him as one of the “sixteen revolutionaries who made America.”

Ray is principal inventor of the first CCD flat-bed scanner, the first omni-font optical character recognition, the first print-to-speech reading machine for the blind, the first text-to-speech synthesizer, the first music synthesizer capable of recreating the grand piano and other orchestral instruments, and the first commercially marketed large-vocabulary speech recognition.

Among Kurzweil’s many honors, he received the 2015 Technical Grammy Award for outstanding achievements in the field of music technology; he is the recipient of the National Medal of Technology, was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, holds twenty-one honorary Doctorates, and honors from three U.S. presidents.

Kurzweilism

The key to be successful as an inventor in 1980s is timing, [you have] to be in right place at right time.

People intuition about future is linear even though they have seen many examples of exponential progressions.

65 million years ago, something strange happen. There was sudden violent change to the environment, we now call it Cretaceous extinction event. There’s been debate what caused it. It was so worldwide phenomenon as it was when dinasours went extinct and almost 75% of all animals and plant species went extinct. That’s when mammals overtook their ecological niche so to anthropomorphize biological evolution said to itself this neocortex is pretty good stuff and it began to grow. So, now mammals got bigger, brains got bigger at even faster pace taking larger fraction of their body. The neocortex got bigger even at faster than that and developed these curvatures that are distinctive of a primate brain basically to increase its surface area but if you stretched it out the human neocortex is still a flat structure. It’s about the size of table napkin just as thin. It created primates which became dominance in their ecological niche.

Then something else happen 2 million years ago, biological evolution decided to increase the neocortex even further and increase the size of enclosure and basically filled up the frontal cortex with our big skulls with more neocortex.

Exponential growth is seductive, starting out slowly and virtually unnoticeably, but beyond the knee of the curve it turns explosive and profoundly transformative. The future is widely misunderstood. Our forebears expected it to be pretty much like their present, which had been pretty much like their past.

Exponential trends did exist one thousand years ago, but they were at that very early stage in which they were so flat and so slow that they looked like no trend at all. As a result, observers’ expectation of an unchanged future was fulfilled. Today, we anticipate continuous technological progress and the social repercussions that follow. But the future will be far more surprising than most people realize, because few observers have truly internalized the implications of the fact that the rate of change itself is accelerating. Most long-range forecasts of what is technically feasible in future time periods dramatically underestimate the power of future developments because they are based on what I call the “intuitive linear” view of history rather than the “historical exponential” view.

The twentieth century was gradually speeding up to today’s rate of progress; its achievements, therefore, were equivalent to about twenty years of progress at the rate in 2000. We’ll make another twenty years of progress in just fourteen years (by 2014), and then do the same again in only seven years. To express this another way, we won’t experience one hundred years of technological advance in the twenty-first century; we will witness on the order of twenty thousand years of progress (again, when measured by today’s rate of progress), or about one thousand times greater than what was achieved in the twentieth century.

People intuitively assume that the current rate of progress will continue for future periods. Even for those who have been around long enough to experience how the pace of change increases over time, unexamined intuition leaves one with the impression that change occurs at the same rate that we have experienced most recently. From the mathematician’s perspective, the reason for this is that an exponential curve looks like a straight line when examined for only a brief duration. As a result, even sophisticated commentators, when considering the future, typically extrapolate the current pace of change over the next ten years or one hundred years to determine their expectations. This is why I describe this way of looking at the future as the “intuitive linear” view.

But a serious assessment of the history of technology reveals that technological change is exponential. Exponential growth is a feature of any evolutionary process, of which technology is a primary example. You can examine the data in different ways, on different timescales, and for a wide variety of technologies, ranging from electronic to biological, as well as for their implications, ranging from the amount of human knowledge to the size of the economy. The acceleration of progress and growth applies to each of them. Indeed, we often find not just simple exponential growth, but “double” exponential growth, meaning that the rate of exponential growth (that is, the exponent) is itself growing exponentially.

Indeed, almost everyone I meet has a linear view of the future. That’s why people tend to overestimate what can be achieved in the short term (because we tend to leave out necessary details) but underestimate what can be achieved in the long term (because exponential growth is ignored).

Quotes

Life begins at a billion examples.

Stories

I came first to MIT in 1952 when I was 14, I became exicted about Artificial Intelligence. It had gotten it’s name 6 years earlier in 1956 Dartmouth Conference by Marvin Minsky and John McCarthy. So, I wrote Minsky a letter, there was no email back then and he invited me up. He spent all day with me as if he had nothing else to do. He was consummate educator. AI firld had already bifurcated into two warring camps, the symbolic school which Minsky was associated with and the connectionist school was not widely known. In fact it’s still not widely known that Minsky actually invented the neural nets in 1953 but he had become largely negative about it because there was a lot of hype that these giant brains could solve any problem.

When I went to MIT in mid 1960, in fact I went to MIT as it was so advanced that it had a computer, many colleges didn’t have one. It was IBM 7094, it had 32K words of memory of 36 bit words to 150K of storage. Thousand of professors and students would share that machine. Your smartphone is billions of times powerful and millions of times cheaper many billion timefold in price-performance.

I have been futurist for long time that was not my primary interest, I wanted to be inventor when I was 5.

In 2012, Larry Page read my book and he liked it. So, I met him in Essen for investment in a company that I had started a couple of weeks earlier to develop my ideas commercially because that’s how I went about things as a serial entrepreneur.

Larry: Well, we’ll invest but let me give you a better idea why don’t you do it here in Google? We have billion pictures of dogs and cats and we got lot of other data and lots of computers and lots of talent, all of which is true.

Ray : I don’t know I just started this company to develop this.

Larry: Well, we will buy your company.

Ray: How are you going to value a company that hasn’t done anything just started a couple of weeks ago?.

Larry: We can value anything.

On Marvin Minsky

I knew Marvin for 53 years and had the opportunity and honor of having many conversations with him and I will say the topic of each of those conversations was different and he really did take delight in ideas as a general concept.

When I was 14, 1962, I wrote him a letter and he said yeah come on up and I wanted to talk to him but I had some ideas about computer models of music. So, he spent it seemed to me like all day like he had nothing else to do. That really was emblematic of Marvin Minsky it was the ultimate educator he loved spending time talking. So actually, that brings up another thought which is, a lot of his ideas and profound thoughts are kind of in the wind somewhere they’ve not been documented that’s why it’s useful to have this kind of remembrance. As I was leaving, he asked, “Are you going back to New York?” and I said, “Well I’m actually going to Cornell to see Frank Rosenblatt.” He didn’t like that. He was not anti-connectionist. So I’m going to come back to that but he did feel the perceptron was getting too much hype and that it didn’t generalize. That was a key issue actually in connectionism, didn’t get resolved till decades later.

So 1965, I came to MIT there really two reasons one was to study with professor Minsky who did become my mentor. The other was MIT was so advanced at that time that it actually had a computer which the other schools didn’t. It was IBM 7094, it had 32K words of memory of 36 bit words to 150K of storage. I did take my favorite course, the course that Minsky had started Mathematical Models Of Computation and it’s actually the only course number I remember 6.253. That was the first year he didn’t teach it himself but it’s a wonderful course on the mathematics of computation. So I’ll jump then to 1997, Marvin and I had given a talk at some function I don’t remember. So we went out to dinner with my then 11 year old daughter and Ted selca mentioned mentioned his interest in silverware structures. Amy and Marvin started building structures from from the silverware but apparently some new idea came up and I’m not sure were so maybe it probably came from both of them but Marvin was very excited about this new discovery because he had not realised this before. So it turns out, the soup spoon and the fork make us stable structures, tea spoon doesn’t work quite so well. But soup spoon, it’s curved and you put it between the prongs of a fork and it stays stable but the fork actually has four prongs, so you can put another soup spoon and now you’ve got a tripod and the tripod will stand there stably and you have another slot because there’s four prongs and you’ve only used two of them out of the three slots so you could build these different tripods and then connect them together with a knife by putting that in the third spot and now you have a stable structure on top of that you can build the next level. So, he was very excited about this and what I found noteworthy, he wasn’t treating Amy like okay this is fun I’m playing with a child. I mean he treated her like she was another professor or graduate student and it didn’t matter he didn’t register on him people’s credentials is really what you could bring to the table.

So he remained my mentor. We had many conversations as I mentioned they were quite diverse. I remember the last one I had was of more than a few minutes. It was a lengthy conversation which actually was on connectionism and I had some ideas on a particular issue that was going to be in the book I was writing. He was now actually quite positive about it. Not most people know that he was actually an early pioneer in Connectionist in 1951. He wrote what I think is the first neural net. I’m not certain of that, it certainly was one of the first ones and really introduced the field of neural nets. He felt that the perceptron was getting too much attention because it didn’t generalize and there was a lot of hype in the press about how it could have deep abstract thoughts and and generalize on the patterns that had learned and he felt to just learn templates and Rosenblatt’s sort of one layer perceptrons that’s really basically what it did. There was a thought that if you add layers you can have the output of one layer of a neural net feed into the next layer and you can have multiple layers. It was felt that you have more layers it would more it would generalize to a great extent and you’d have more abstract thinking. However up until maybe five or six years ago, we couldn’t go beyond three or four levels or layers, the reason for that was actually a mathematical problem you have to keep the each the output of each layer is kind of surface and in a you know a thousand dimensional space and you have to keep the surface convex otherwise it collapses eventually and they weren’t able to to solve that mathematical problem go beyond four levels. Hinton and some other researchers solve that mathematical problem now you could go to many levels so a big accusation against AI which concerned Minsky is that AI can’t even tell the difference between the dog and a cat and neither the symbolic school or the connection school could solve that problem. Well the concept of a cat is pretty abstract and if that really doesn’t emerge until the 15 layer of a neural net but now we can actually go to 15 to 20 levels. So now we can actually tell the difference between a dog and a cat and other concepts as well. He took note of that and was actually very impressed and excited about connectionism “not that it would do everything” but that now finally these claims of the perceptron from the early 60s were coming true. He also said he regretted the apparent success of the book perceptrons that he wrote with Seymour Papert. The the last chapter is a theorem that a perceptron can’t solve the connectedness problem and on the cover of the book there’s two images that look very similar but one’s connected and one isn’t and so it’s actually not an easy problem for humans itself but if a perceptron can’t even solve that problem then obviously it’s not a very good technique at least, that’s what people derive from it. But he said,”it was really a challenge to the connectionist field” and that challenge finally got kind of answered just recently and it was not his intention to dry up all the funding which was one of the results of the book and he regretted that. When computer took the Go championship recently my first thought is oh I wonder what the Minsky thinks of this because the Chess Championship it was largely a symbolic technique of the minimax algorithm and now this was really a neural net achievement and I would have liked to have gotten his thoughts on it. In my group at Google were creating chatbots, where you can feed in the writings of someone like their blog and actually get a chatbot that sort of expresses their ideas and, has their style of personality. So the idea came up, gee, why don’t we feed in all of Minsky’s ideas that would really be a very interesting chatbot but one of the problems is that we discussed is as I mentioned a few minutes ago most of his thoughts are in the wind somewhere. He’s written beautiful books “Society of Mind” and the “Emotion Machine”, are brilliant books of computer science, mathematics, psychology, and poetry, and certainly there is material of his there are some recorded speeches but really the most profound words of his were said in the kinds of settings that people have shared with you tonight conversations, you know like might be taking place in that room. It actually would be a good idea if someone were to try to capture all the different find all the videos of that do exist and audio recordings and get people’s reminiscences.

I’m considered a futurist. I like to make predictions that are not next week some or next month I’m not going to try to predict the election but I predict by 2045 we’ll be able to alive Marvin so we can all resume our conversations with him at that time.