Richard Feynman

This a collection of almost everything including stories, lessons, short quotes which I will keep updating often. Happy Learning!

Feynman’s last words I’d hate to die twice. It’s so boring.

The imagination of nature is far, far greater than the imagination of man.

Feel free to jump anywhere,

Feynmanism

The fact that I beat a drum has nothing to do with the fact that I do theoretical physics. Theoretical physics is a human endeavor, one of the higher developments of human beings – and this perpetual desire to prove that people who do it are human by showing that they do other things that a few other humans do (like playing bongo drums) is insulting to me.

It’s interesting some people find science interesting while some find it dull and difficult. I don’t know why it is. I think people lose a lot of pleasure who find science dull. In case of science, I think on of the things it makes it difficult is it takes a lot of imagination. It’s very hard to imagine all crazy things.

The things with which we concern ourselves in science appear in myriad forms, and with a multitude of attributes. For example, if we stand on the shore and look at the sea, we see the water, the waves breaking, the foam, the sloshing motion of the water, the sound, the air, the winds and the clouds, the sun and the blue sky, and light; there is sand and there are rocks of various hardness and permanence, color and texture. There are animals and seaweed, hunger and disease, and the observer on the beach; there may be even happiness and thought. Any other spot in nature has a similar variety of things and influences. It is always as complicated as that, no matter where it is. Curiosity demands that we ask questions, that we try to put things together and try to understand this multitude of aspects as perhaps resulting from the action of a relatively small number of elemental things and forces acting in an infinite variety of combinations.

For example: Is the sand other than the rocks? That is, is the sand perhaps nothing but a great number of very tiny stones? Is the moon a great rock? If we understood rocks, would we also understand the sand and the moon? Is the wind a sloshing of the air analogous to the sloshing motion of the water in the sea? What common features do different movements have? What is common to different kinds of sound? How many different colors are there? And so on. In this way we try gradually to analyze all things, to put together things which at first sight look different, with the hope that we may be able to reduce the number of different things and thereby understand them better.

How does a person answer “Why something happens?” For example, Aunt Mini is hospital. Why? Because she slipped, went out on the ice and broke her hip. That satisfies people but it wouldn’t satisy someone who came from another planet and would knew nothing about first when you break your hip why do you go to hospital? When you explain why you have to be in some framework that you allow something to be true. Otherwise you are perpetually asking why.

How do we look for new law? In general we look for a new law by the following process. First we guess it. Then we compute the consequences of the guess to see what would be implied if this law that we guessed is right. Then we compare the result of the computation to nature, with experiment or experience, compare it directly with observation, to see if it works. If it disagrees with experiment it’s wrong. In that simple statement is the key to science. It does not make any difference how beautiful your guess is. It does not make any difference how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is – if it disagrees with experiment it is wrong. That is all there is to it.

I have approximate answers and possible beliefs and different degrees of certainity of different things but I am not absolutely sure of anything and the many things I don’t know about.

I don’t feel frightened by not knowing things. By being lost in the mysterious universe without having any purpose which the way it really is as far I as I can tell possibly.

The best way to teach is have no philosophy. It is to be chaotic and confusing in the sense that you use every possible way of doing it.

I want to discuss now the art of guessing nature’s laws. It is an art. How is it done? One way you might suggest is to look at history to see how the other guys did it. So we look at history. We must start with Newton. He had a situation where he had incomplete knowledge, and he was able to guess the laws by putting together ideas which were all relatively close to experiment; there was not a great distance between the observations and the tests. That was the first way, but today it does not work so well.

The next guy who did something great was Maxwell, who obtained the laws of electricity and magnetism. What he did was this. He put together all the laws of electricity, due to Faraday and other people who came before him, and he looked at them and realized that they were mathematically inconsistent. In order to straighten it out he had to add one term to an equation. He did this by inventing for himself a model of idler wheels and gears and so on in space. He found what the new law was – but nobody paid much attention because they did not believe in the idler wheels. We do not believe in the idler wheels today, but the equations that he obtained were correct. So the logic may be wrong but the answer right.

In the case of relativity the discovery was completely different. There was an accumulation of paradoxes; the known laws gave inconsistent results. This was a new kind of thinking, a thinking in terms of discussing the possible symmetries of laws. It was especially difficult, because for the first time it was realized how long something like Newton’s laws could seem right, and still ultimately be wrong. Also it was difficult to accept that ordinary ideas of time and space, which seemed so instinctive, could be wrong.

Quantum mechanics was discovered in two independent ways – which is a lesson. There again, and even more so, an enormous number of paradoxes were discovered experimentally, things that absolutely could not be explained in any way by what was known. It was not that the knowledge was incomplete, but that the knowledge was too complete. Your prediction was that this should happen – it did not. The two different routes were one by Schrödinger,* who guessed the equation, the other by Heisenberg, who argued that you must analyse what is measurable. These two different philosophical methods led to the same discovery in the end.

More recently, the discovery of the laws of the weak decay I spoke of, when a neutron disintegrates into a proton, an electron and an anti-neutrino – which are still only partly known – add up to a somewhat different situation. This time it was a case of incomplete knowledge, and only the equation was guessed. The special difficulty this time was that the experiments were all wrong. How can you guess the right answer if, when you calculate the result, it disagrees with experiment? You need courage to say the experiments must be wrong. I will explain where that courage comes from later.

Suppose you have two theories, A and B, which look completely different psychologically, with different ideas in them and so on, but that all the consequences that are computed from each are exactly the same, and both agree with experiment. The two theories, although they sound different at the beginning, have all consequences the same, which is usually easy to prove mathematically by showing that the logic from A and B will always give corresponding consequences. Suppose we have two such theories, how are we going to decide which one is right? There is no way by science, because they both agree with experiment to the same extent. So two theories, although they may have deeply different ideas behind them, may be mathematically identical, and then there is no scientific way to distinguish them. However, for psychological reasons, in order to guess new theories, these two things may be very far from equivalent, because one gives a man different ideas from the other. By putting the theory in a certain kind of framework you get an idea of what to change. There will be something, for instance, in theory A that talks about something, and you will say, ‘ll change that idea in here’. But to find out what the corresponding thing is that you are going to change in B may be very complicated – it may not be a simple idea at all. In other words, although they are identical before they are changed, there are certain ways of changing one which looks natural which will not look natural in the other. Therefore psychologically we must keep all the theories in our heads, and every theoretical physicist who is any good knows six or seven different theoretical representations for exactly the same physics. He knows that they are all equivalent, and that nobody is ever going to be able to decide which one is right at that level, but he keeps them in his head, hoping that they will give him different ideas for guessing.

This picture of atom is very beautiful one that you can keep looking all kind of things this way. You see a little(tiny) drop of water and the atoms attract each other, they like to be next to each other, they want as many partners as they can ghet. Now the guys that are at the surface have partners only at one side and the air at other side so they are trying to get in. You could imagine this team of people all moving very fast all trying to get as many partners as they can, they guys at the edge are very unhappy and nervous and they keep pounding in trying to get in makes it a tight bowl inside of flat and that’s what surface tension is.

If you cool of the water so the jiggling of atoms is less and less, they jiggle slow and slow. Then the atoms get stuck in a place, they like to be with their friends, there is force of attraction and they get packed. Together they are not rolling over each other, they are in nice pattern like a oranges in crate. All atoms just jiggling in place not having enough motion to get loose of their own place and break the structure down. That’s the structure of solid like ice. On other hand, if you heat that harder they begin to get loose and they roll all over each other and that’s the liquid and if you heat that still harder then they bounce harder. They simply bounce apart each other (overcoming the force of attraction) and are group of atoms, a molecule flying at high speed. This is the gas we call steam.

The atoms like each other at different degrees. Oxygen for instance in the air would like to be next to carbon and they snap to each other when they get close. If they are not too close though they repel and they go apart so they don’t know they could stand together. The situation is similar to a ball rolling up the hill with mountain having a deep hole like in valcano, so when we push the ball up it goes up and comes down not completely going up unless we push it harder. The same situation is with oxygen molecule. But when we bring wood(contains carbon) in oxygen from air, the carbon from wood in tree and oxygen comes and hits carbon but no hard enough, it just goes away again. The air is always coming and nothing is happening. If you can get it faster by heating it up somehow, get it started some of them come fast (they go over the top of mountain) they come close enough to carbon and snap in and that creates a lot of jiggly motion and that might hit some other atom, then those go faster(so they could climb up) and make other atoms of carbon jiggle and so on. What you get is a terrible catastrophe which is one after another these things are going faster and faster and snapping in and whole thing is changing. That catastrophe is fire🔥.

Trees come of air not the ground. The carbon dioxide in the air goes into the tree and they changes it kicking out the oxygen and leaving the carbon with water. Water comes of the ground but water too came out of sky you see. So, in fact most of the trees are out of the air. There is a little bit from ground some minerals and so forth.

How is the tree so smart to take out the carbon and kick oxygen from carbon dioxide so easily? Ahh the nature. Life has some mysterious fuss. The sun is shining and it’s the sunlight that comes down and that knocks this oxygen away from carbon. So, it takes sunlight to get to plant to work. Sun is all time doing this work of seperating the oxygen away from the carbon and spitting the oxygen as some kind of terrible byproduct back into air and leaving the carbon and water and stuff to make the substance to the tree. Then when we take the substance of the tree and stick it in fireplace, all the oxygen made by these trees and all the carbon (wood from tree) would much prefer to be close together again. And once you get the heat to get it started, it continues and makes a awful lot of activity while it’s going back together again. All this nice light and everything comes out and everything is being undone and you get carbon dioxide back from carbon and oxygen and the light and heat that’s coming out, that’s light and heat of sun that went in. So, it’s sort of stored sun that’s coming out when you burn a log.

There is no special miracle, talent, ability to understand quantum mechanics or to imagine electromagnetic fields. It comes without practice in reading and learning. If you say, you take a ordinary person who is wiling to devote a great deal of time and study and work and think and Mathematics then he has become a scientist.

One kid says to me, “See that bird? What kind of bird is that?” </br> I said, “I haven’t the slightest idea what kind of a bird it is.”</br> He says, “It’a brown-throated thrush. Your father doesn’t teach you anything!”</br> But it was the opposite. He [Feynman’s father] had already taught me: “See that bird?” he says. “It’s a Spencer’s warbler.” (I knew he didn’t know the real name.) “Well, in Italian, it’s a Chutto Lapittida. In Portuguese, it’s a Bom da Peida… You can know the name of that bird in all the languages of the world, but when you’re finished, you’ll know absolutely nothing whatever about the bird! You’ll only know about humans in different places, and what they call the bird. So let’s look at the bird and see what it’s doing — that’s what counts.” (I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.)

It is not unscientific to make a guess, although many people who are not in science think it is. Some years ago I had a conversation with a layman about flying saucers – because I am scientific I know all about flying saucers! I said ‘I don’t think there are flying saucers’. So my antagonist said, ‘Is it impossible that there are flying saucers? Can you prove that it’s impossible?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘I can’t prove it’s impossible. It’s just very unlikely’. At that he said, ‘You are very unscientific. If you can’t prove it impossible then how can you say that it’s unlikely?’ But that is the way that is scientific. It is scientific only to say what is more likely and what less likely, and not to be proving all the time the possible and impossible. To define what I mean, I might have said to him, ‘Listen, I mean that from my knowledge of the world that I see around me, I think that it is much more likely that the reports of flying saucers are the results of the known irrational characteristics of terrestrial intelligence than of the unknown rational efforts of extra-terrestrial intelligence’. It is just more likely, that is all. It is a good guess. And we always try to guess the most likely explanation, keeping in the back of the mind the fact that if it does not work we must discuss the other possibilities.

How can we guess what to keep and what to throw away? We have all these nice principles and known facts, but we are in some kind of trouble: either we get the infinities, or we do not get enough of a description – we are missing some parts. Sometimes that means that we have to throw away some idea; at least in the past it has always turned out that some deeply held idea had to be thrown away. The question is, what to throw away and what to keep. If you throw it all away that is going a little far, and then you have not much to work with. After all, the conservation of energy looks good, and it is nice, and I do not want to throw it away. To guess what to keep and what to throw away takes considerable skill. Actually it is probably merely a matter of luck, but it looks as if it takes considerable skill.

What do we mean by “understanding” something? We can imagine that this complicated array of moving things which constitutes “the world” is something like a great chess game being played by the gods, and we are observers of the game. We do not know what the rules of the game are; all we are allowed to do is to watch the playing. Of course, if we watch long enough, we may eventually catch on to a few of the rules. The rules of the game are what we mean by fundamental physics. Even if we knew every rule, however, we might not be able to understand why a particular move is made in the game, merely because it is too complicated and our minds are limited. If you play chess you must know that it is easy to learn all the rules, and yet it is often very hard to select the best move or to understand why a player moves as he does. So it is in nature, only much more so; but we may be able at least to find all the rules. Actually, we do not have all the rules now. (Every once in a while something like castling is going on that we still do not understand.) Aside from not knowing all of the rules, what we really can explain in terms of those rules is very limited, because almost all situations are so enormously complicated that we cannot follow the plays of the game using the rules, much less tell what is going to happen next. We must, therefore, limit ourselves to the more basic question of the rules of the game. If we know the rules, we consider that we “understand” the world.

How can we tell whether the rules which we “guess” at are really right if we cannot analyze the game very well? There are, roughly speaking, three ways. First, there may be situations where nature has arranged, or we arrange nature, to be simple and to have so few parts that we can predict exactly what will happen, and thus we can check how our rules work. (In one corner of the board there may be only a few chess pieces at work, and that we can figure out exactly.)

A second good way to check rules is in terms of less specific rules derived from them. For example, the rule on the move of a bishop on a chessboard is that it moves only on the diagonal. One can deduce, no matter how many moves may be made, that a certain bishop will always be on a red square. So, without being able to follow the details, we can always check our idea about the bishop’s motion by finding out whether it is always on a red square. Of course it will be, for a long time, until all of a sudden we find that it is on a black square (what happened of course, is that in the meantime it was captured, another pawn crossed for queening, and it turned into a bishop on a black square). That is the way it is in physics. For a long time we will have a rule that works excellently in an overall way, even when we cannot follow the details, and then some time we may discover a new rule. From the point of view of basic physics, the most interesting phenomena are of course in the new places, the places where the rules do not work—not the places where they do work! That is the way in which we discover new rules.

The third way to tell whether our ideas are right is relatively crude but probably the most powerful of them all. That is, by rough approximation. While we may not be able to tell why Alekhine moves this particular piece, perhaps we can roughly understand that he is gathering his pieces around the king to protect it, more or less, since that is the sensible thing to do in the circumstances. In the same way, we can often understand nature, more or less, without being able to see what every little piece is doing, in terms of our understanding of the game.

The difficulties of science are to a large extent the difficulties of notations, the units, and all the other artificialities which are invented by man, not by nature.

FEYNMAN learning strategy in THREE points: 1. Continually ask “Why?” 2. When you learn something, learn it to where you can explain it to a child. 3. Instead of arbitrarily memorizing things, look for the explanation that makes it obvious.

FOUR Productivity FEYNMAN- strategies: i) Stop trying to know-it-all. ii) Don’t worry about what others are thinking. iii) Don’t think about what you want to be, but what you want to do. iv) Have a sense of humor and talk honestly.

It doesn’t matter how beautiful your theory is, it doesn’t matter how smart you are. If it doesn’t agree with experiment, it’s wrong. In that simple statement is the key to science.

To those who do not know mathematics it is difficult to get across a real feeling as to the beauty, the deepest beauty, of nature. If you want to learn about nature, to appreciate nature, it is necessary to understand the language that she speaks in.

Quotes

What I cannot create I do not understand.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.

The trick to learning is enjoying.

Look for the simplest, most elementary solution to a problem that was possible. If it wasn’t possible, you use something fancier.

I’m smart enough to know that I’m dumb.

I can live with doubt and uncertainty and not knowing. I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong.

He was the most original mind of his generation — Freeman Dyson

There are two types of genius. Ordinary geniuses do great things, but they leave you room to believe that you could do the same if only you worked hard enough. Then there are magicians, and you can have no idea how they do it. Feynman was a magician. — Hans Bethe

Both a showman and a very practical thinker. It is unlikely that the world will see another Richard Feynman. — Paul Davies

I learned very early the difference between knowing the name of something and knowing something.

Just the runner gets kick out of sweating, I get the run out of thinking.

I think nature’s imagination is so much greater than man, she’s never going to let us relax.

The deeper a thing is, the more interesting it is.

I was a ordinary person who studied hard. There is no miracle people.

Study hard what interests you the most in the most undisciplined, irreverent and original manner possible.

If you want to master something, teach it.

I don’t know anything, but I do know that everything is interesting if you go into it deeply enough.

If our small minds, for some convenience, divide this universe, into parts — physics, biology, geology, astronomy, psychology, and so on — remember that nature does not know it!

I would rather have questions that cannot be answered than answers that cannot be questioned.

Stories

When I was a kid, I noticed that when I pumped the tyres of bicycle, you learn a lot by having a bicycle, pump up the tyre the pump would get hot. As the pump comes down the atoms are coming up against it and are bouncing up as the pump is moving in, the ones(atoms) that are coming off are having the biggest speed than the ones that are coming in. As it comes down, each time they collide it speeds them up and so they are harder. When you compress the gas it heats and when you pull the piston back out, then the atoms which are coming fast at the piston it loses engery. As you put the piston out, the atoms lose their speed and they cool off and gases cool when they expand. I don’t wanna take this stuff seriously, I think we should have fun imagining it and not worry about it. There is no teacher to ask you a question in the end. Otherwise it’s a horrible subject.

I went through a scientific school MIT and then in fraternity when you first join, if you think you are smart keep you from feeling that you are too smart by giving you what look like simple questions to try to figure out what actually happens. It’s like training for imagination. Once you learn them when somebody comes to you with wonderful puzzle you look at them, quietly 2 or 3 seconds to show that you were thinking and then you come up with this answer to astonish your friends but the fact was that of course you were trained by your fraternity brothers as how to answer these things early on.

When I was a boy my father telling me things. So, I tried telling my son things that were interesting about the world. We he was really small I used to walk him to bed, I would tell him stories and I would make up stories about little people and they go through these woods which has great long tall blue things like tree without leaves and only one stalk and they had to walk in between inside. He gradually catch on that was the nap of blue rug and he loved this game because I would discuss all these things from odd point of view. Then I have a daughter, I tried the same thing. But my daughters personality was different. She didn’t want to hear these stories, she wanted me to read the stories that were in the book repeated. So, a very good method in teaching children about science is to make up these stories of these little people.

A story that physicist and writer Alan Lightman told Nautilus: Richard Feynman came up with the idea for spontaneous emission before Hawking. Here is Lightman in his own words:

One day at lunch in the Caltech cafeteria, I was with two graduate students, Bill Press and Saul Teukolsky, and Feynman. Bill and Saul were talking about a calculation they had just done. It was a theoretical calculation, purely mathematical, where they looked at what happens if you shine light on a rotating black hole. If you shine it at the right angle, the light will bounce off the black hole with more energy than it came in with. The classical analogue is a spinning top. If you throw a marble at the top at the right angle, the marble will bounce off the top with more velocity than it came in with. The top slows down and the energy, the increased energy of the marble, comes from the spin of the top. As Bill and Saul were talking, Feynman was listening.

We got up from the table and began walking back through the campus. Feynman said, “You know that process you’ve described? It sounds very much like stimulated emission.” That’s a quantum process in atomic physics where you have an electron orbiting an atom, and a light particle, a photon, comes in. The two particles are emitted and the electron goes to a lower energy state, so the light is amplified by the electron. The electron decreases energy and gives up that extra energy to sending out two photons. Feynman said, “What you’ve just described sounds like stimulated emission. According to Einstein, there’s a well-known relationship between stimulated emission and spontaneous emission.”

Spontaneous emission is when you have an electron orbiting an atom and it just emits a photon all by itself, without any light coming in, and goes to a lower energy state. Einstein had worked out this relationship between stimulated and spontaneous emission. Whenever you have one, you have the other, at the atomic level. That’s well known to graduate students of physics. Feynman said that what Bill and Saul were describing sounded like simulated emission, and so there should be a spontaneous emission process analogous to it.

We’d been wandering through the campus. We ended up in my office, a tiny little room, Bill, Saul, me, and Feynman. Feynman went to the blackboard and began working out the equations for spontaneous emission from black holes. Up to this point in history, it had been thought that all black holes were completely black, that a black hole could never emit on its own any kind of energy. But Feynman had postulated, after listening to Bill and Saul talk at lunch, that if a spinning black hole can emit with light coming in, it can also emit energy with nothing coming in, if you take into account quantum mechanics.

After a few minutes, Feynman had worked out the process of spontaneous emission, which is what Stephen Hawking became famous for a year later. Feynman had it all on my blackboard. He wasn’t interested in copying down what he’d written. He just wanted to know how nature worked, and he had just learned that isolated black holes are capable of emitting energy when you take into account quantum effects. After he finished working it out, he brushed his hands together to get the chalk dust off them, and walked out of the office.

After Feynman left, Bill and Saul and I were looking at the blackboard. We were thinking it was probably important, not knowing how important. Bill and Saul had to go off to some appointment, and so they left the office. A little bit later, I left. But that night I realized this was a major thing that Feynman had done and I needed to hurry back to my office and copy down the equations. But when I got back to my office in the morning, the cleaning lady had wiped the blackboard clean.

Leonard Susskind: My friend Richard Feynman

This is transcript of the TED Talk by Leonard Susskind. Shamlessly copied the transcript from ted transcribers(?), thank you ted.

I decided when I was asked to do this that what I really wanted to talk about was my friend, Richard Feynman. I was one of the fortunate few that really did get to know him and enjoyed his presence. And I’m going to tell you about the Richard Feynman that I knew. I’m sure there are people here who could tell you about the Richard Feynman they knew, and it would probably be a different Richard Feynman.

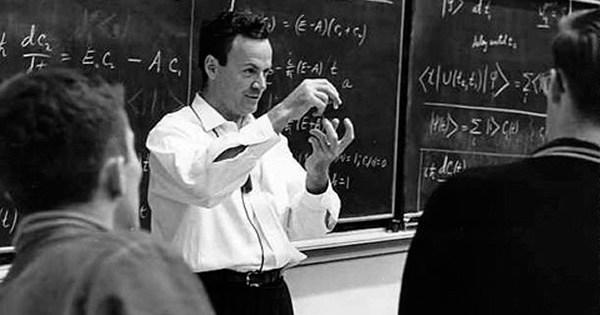

Richard Feynman was a very complex man. He was a man of many, many parts. He was, of course, foremost, a very, very, very great scientist. He was an actor. You saw him act. I also had the good fortune to be in those lectures, up in the balcony. They were fantastic. He was a philosopher. He was a drum player. He was a teacher par excellence. Richard Feynman was also a showman, an enormous showman. He was brash, irreverent. He was full of macho, a kind of macho one-upmanship. He loved intellectual battle. He had a gargantuan ego. But the man had, somehow, a lot of room at the bottom. And what I mean by that is a lot of room, in my case – I can’t speak for anybody else, but in my case – a lot of room for another big ego. Well, not as big as his, but fairly big. I always felt good with Dick Feynman.

It was always fun to be with him. He always made me feel smart. How can somebody like that make you feel smart? Somehow he did. He made me feel smart. He made me feel he was smart. He made me feel we were both smart, and the two of us could solve any problem whatever. And in fact, we did sometimes do physics together. We never published a paper together, but we did have a lot of fun.

He loved to win, win these little macho games we would sometimes play. And he didn’t only play them with me, but with all sorts of people. He would almost always win. But when he didn’t win, when he lost, he would laugh and seem to have just as much fun as if he had won.

I remember once he told me a story about a joke the students played on him. I think it was for his birthday – they took him for lunch to a sandwich place in Pasadena. It may still exist; I don’t know. Celebrity sandwiches was their thing. You could get a Marilyn Monroe sandwich. You could get a Humphrey Bogart sandwich. The students went there in advance, and arranged that they’d all order Feynman sandwiches. One after another, they came in and ordered Feynman sandwiches. Feynman loved this story. He told me this story, and he was really happy and laughing. When he finished the story, I said to him, “Dick, I wonder what would be the difference between a Feynman sandwich and a Susskind sandwich.” And without skipping a beat at all, he said, “Well, they’d be about the same. The only difference is a Susskind sandwich would have a lot more ham.” “Ham” as in bad actor.

Well, I happened to have been very quick that day, and I said, “Yeah, but a lot less baloney.”

The truth of the matter is that a Feynman sandwich had a load of ham, but absolutely no baloney. What Feynman hated worse than anything else was intellectual pretense – phoniness, false sophistication, jargon. I remember sometime during the mid-‘80s, Dick and I and Sidney Coleman would meet a couple of times up in San Francisco – at some very rich guy’s house – up in San Francisco for dinner. And the last time the rich guy invited us, he also invited a couple of philosophers. These guys were philosophers of mind. Their specialty was the philosophy of consciousness. And they were full of all kinds of jargon. I’m trying to remember the words – “monism,” “dualism,” categories all over the place. I didn’t know what those meant, neither did Dick or Sydney, for that matter.

And what did we talk about? Well, what do you talk about when you talk about minds? There’s one obvious thing to talk about: Can a machine become a mind? Can you build a machine that thinks like a human being that is conscious? We sat around and talked about this – we of course never resolved it. But the trouble with the philosophers is that they were philosophizing when they should have been science-ophizing. It’s a scientific question, after all. And this was a very, very dangerous thing to do around Dick Feynman.

Feynman let them have it – both barrels, right between the eyes. It was brutal; it was funny – ooh, it was funny. But it was really brutal. He really popped their balloon. But the amazing thing was – Feynman had to leave a little early; he wasn’t feeling too well, so he left a little bit early. And Sidney and I were left there with the two philosophers. And the amazing thing is these guys were flying. They were so happy. They had met the great man; they had been instructed by the great man; they had an enormous amount of fun having their faces shoved in the mud … And it was something special. I realized there was something just extraordinary about Feynman, even when he did what he did.

Dick – he was my friend; I did call him Dick – Dick and I had a little bit of a rapport. I think it may have been a special rapport that he and I had. We liked each other; we liked the same kind of things. I also like the intellectual macho games. Sometimes I would win, mostly he would win, but we both enjoyed them. And Dick became convinced at some point that he and I had some kind of similarity of personality. I don’t think he was right. I think the only point of similarity between us is we both like to talk about ourselves. But he was convinced of this. And the man was incredibly curious. And he wanted to understand what it was and why it was that there was this funny connection.

And one day, we were walking. We were in France, in Les Houches. We were up in the mountains, 1976. And Feynman said to me, “Leonardo …” The reason he called me “Leonardo” is because we were in Europe, and he was practicing his French.

And he said, “Leonardo, were you closer to your mother or your father when you were a kid?” I said, “Well, my real hero was my father. He was a working man, had a fifth-grade education. He was a master mechanic, and he taught me how to use tools. He taught me all sorts of things about mechanical things. He even taught me the Pythagorean theorem. He didn’t call it the hypotenuse, he called it the shortcut distance.”

And Feynman’s eyes just opened up. He went off like a lightbulb. And he said that he had had basically exactly the same relationship with his father. In fact, he had been convinced at one time that to be a good physicist, it was very important to have had that kind of relationship with your father. I apologize for the sexist conversation here, but this is the way it really happened.

He said he had been absolutely convinced that this was necessary, a necessary part of the growing up of a young physicist. Being Dick, he, of course, wanted to check this. He wanted to go out and do an experiment.

Well, he did. He went out and did an experiment. He asked all his friends that he thought were good physicists, “Was it your mom or your pop that influenced you?” They were all men, and to a man, every single one of them said, “My mother.”

There went that theory, down the trash can of history.

But he was very excited that he had finally met somebody who had the same experience with his father as he had with his father. And for some time, he was convinced this was the reason we got along so well. I don’t know. Maybe. Who knows?

But let me tell you a little bit about Feynman the physicist. Feynman’s style – no, “style” is not the right word. “Style” makes you think of the bow tie he might have worn, or the suit he was wearing. It’s something much deeper than that, but I can’t think of another word for it. Feynman’s scientific style was always to look for the simplest, most elementary solution to a problem that was possible. If it wasn’t possible, you had to use something fancier. No doubt, part of this was his great joy and pleasure in showing people that he could think more simply than they could. But he also deeply believed, he truly believed, that if you couldn’t explain something simply, you didn’t understand it. In the 1950s, people were trying to figure out how superfluid helium worked.

There was a theory. It was due to a Russian mathematical physicist. It was a complicated theory; I’ll tell you what it was soon enough. It was a terribly complicated theory, full of very difficult integrals and formulas and mathematics and so forth. And it sort of worked, but it didn’t work very well. The only way it worked is when the helium atoms were very, very far apart. And unfortunately, the helium atoms in liquid helium are right on top of each other.

Feynman decided, as a sort of amateur helium physicist, that he would try to figure it out. He had an idea, a very clear idea. He would try to figure out what the quantum wave function of this huge number of atoms looked like. He would try to visualize it, guided by a small number of simple principles. The small number of simple principles were very, very simple. The first one was that when helium atoms touch each other, they repel. The implication of that is that the wave function has to go to zero, it has to vanish when the helium atoms touch each other. The other fact is that in the ground state – the lowest energy state of a quantum system – the wave function is always very smooth; it has the minimum number of wiggles.

So he sat down – and I imagine he had nothing more than a simple piece of paper and a pencil – and he tried to write down, and did write down, the simplest function that he could think of, which had the boundary conditions that the wave function vanish when things touch and is smooth in between. He wrote down a simple thing – so simple, in fact, that I suspect a really smart high-school student who didn’t even have calculus could understand what he wrote down. The thing was, that simple thing that he wrote down explained everything that was known at the time about liquid helium, and then some.

I’ve always wondered whether the professionals – the real professional helium physicists – were just a little bit embarrassed by this. They had their super-powerful technique, and they couldn’t do as well. Incidentally, I’ll tell you what that super-powerful technique was. It was the technique of Feynman diagrams.

He did it again in 1968. In 1968, in my own university – I wasn’t there at the time – they were exploring the structure of the proton. The proton is obviously made of a whole bunch of little particles; this was more or less known. And the way to analyze it was, of course, Feynman diagrams. That’s what Feynman diagrams were constructed for – to understand particles. The experiments that were going on were very simple: you simply take the proton, and you hit it really sharply with an electron. This was the thing the Feynman diagrams were for.

The only problem was that Feynman diagrams are complicated. They’re difficult integrals. If you could do all of them, you would have a very precise theory, but you couldn’t – they were just too complicated. People were trying to do them. You could do a one-loop diagram. Don’t worry about one loop. One loop, two loops – maybe you could do a three-loop diagram, but beyond that, you couldn’t do anything.

Feynman said, “Forget all of that. Just think of the proton as an assemblage, a swarm, of little particles.” He called them “partons.” He said, “Just think of it as a swarm of partons moving real fast.” Because they’re moving real fast, relativity says the internal motions go very slow. The electron hits it suddenly – it’s like taking a very sudden snapshot of the proton. What do you see? You see a frozen bunch of partons. They don’t move, and because they don’t move during the course of the experiment, you don’t have to worry about how they’re moving. You don’t have to worry about the forces between them. You just get to think of it as a population of frozen partons.” This was the key to analyzing these experiments. Extremely effective. Somebody said the word “revolution” is a bad word. I suppose it is, so I won’t say “revolution,” but it certainly evolved very, very deeply our understanding of the proton, and of particles beyond that.

Well, I had some more that I was going to tell you about my connection with Feynman, what he was like, but I see I have exactly half a minute. So I think I’ll just finish up by saying: I actually don’t think Feynman would have liked this event. I think he would have said, “I don’t need this.” But …

How should we honor Feynman? How should we really honor Feynman? I think the answer is we should honor Feynman by getting as much baloney out of our own sandwiches as we can. Thank you.