The title itself should sufficient enough to spoil the fun about what the post is all about.

This will be a first post, a part of series of posts reviewing the paper.

Let’s being with the introduction.

Feel free to jump anywhere,

- Introduction

- Cognitive and neural inspiration in AI

- Problems in two challenges

- Core ingredients of human intelligence

- Footnotes

Introduction

Like any other emerging discipline that once went through an embryo phase, the early development of AI was beset with difficulties. It had been questioned, and underwent many ups and downs. In recent years, stimulus such as the rise of big data, the innovation of theoretical algorithms, the improvement of computing capabilities, and the evolution of network facilities brought revolutionary progresses to the AI industry which has accumulated knowledge for over 50 years. Research and application innovations surrounding AI has entered a new stage of development with unprecedented vigor. In last few years, there seems to be an exponential progress. Much of this progress has come from recent advances in the field of “deep learning” in many domains spanning object detection, recognition, segmentation, speech recognition, synthesis and control. It all began one summer when Krizhevsky et al (2012) trained a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) that nearly halved the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) error rate on most challenging benchmark in image classification contest (ImageNet) organized by Stanford Vision Lab. The media have covered many of the recent achievements of neural networks, often expressing the view that neural networks have achieved this recent success by virtue of their brain-like computation and, therefore, their ability to emulate human learning and human cognition. But the question is, have they? How far can relatively generic neural networks bring us towards the goal of building more human-like learning and thinking machines?

The authors riding this wave of excitement examine “what it means for a machine to learn like a person”. The goal of this paper is to propose a set of core ingredients for building more human-like learning and thinking machines.

Cognitive and neural inspiration in AI

The questions of whether and how AI should relate to human congnitive psychology is older than the terms artificial intelligence and cognitive psychology. Alan Turing pictured the child’s mind as notebook with “rather little mechanism and lot of blank sheets” and the mind of a child-machine as filling the notebook by responding to rewards and punishments, similar to reinforcement learning. Alan Turing suspected that it was easier to build and educate a child-machine than try to fully capture adult human cognition.1

Although cognitive science has not yet converged on a single account of the mind or intelligence, the claim that a mind is a collection of general-purpose neural networks with a few intial constraints is rather extreme in a contemporary congnitive science. The authors propose two challenge problems from machine learning and AI :

1. Learning simple visual concepts

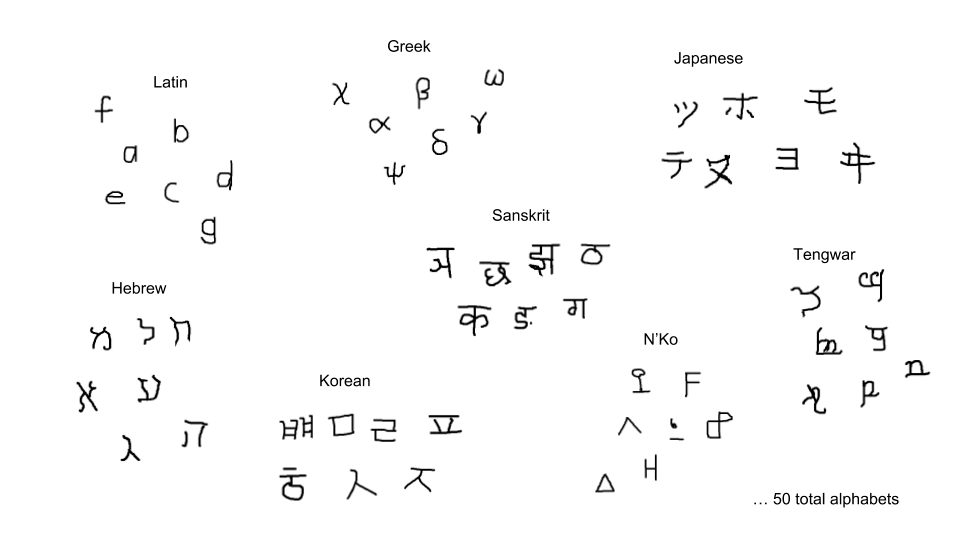

Hofstadter argued that the problem of recognizing characters in all of the ways people do -both handwritten and printed -contains most, if not all, of the fundamental challenges of AI. Whether or not this statement is correct, it highlights the surprising complexity that underlies even “simple” human-level concepts like “letters”.

Character Challenge is tackled by using deep CNN or one-shot learning.Although neural networks may outperform humans on classification tasks (MNIST, Imagenet), it does not mean that they learn and think in the same way. Atleast two important differences: people learn from fewer examples and they learn richer representations. Morever, people learn more than how to do pattern recognition: they learn a concept, that is, a model of the class that allows their acquired knowledge to be flexibly applied in new ways. In addition of recognizing new examples, people can also generate new examples, parse a character into its most important parts and relations, and generate new characters given a small set of related characters. These additional abilities come for free along with the acquisition of the underlying concepts. People learn a lot more from a lot less, and capturing these human-level learning abilities in machines is the Characters Challenge.

The authors reported progress on this challenge using probabilistic program induction2, yet aspects of full human congnitive ability remain out of reach. Additional progresss may come by combining deep learning and probabilistic program induction to tackle even richer versions of the Character Challenge.

2. Learning to play the Atari game Frostbite

In Frostbite, players control an agent (Frostbite Bailey) tasked with constructing an igloo within a time limit. The igloo is built piece by piece as the agent jumps on ice floes in water. The challenge is that the ice floes are in constant motion (movig either left or right), and ice floes only contribute to the construction of the igloo if they are visited in an active state (white, rather than blue). The agent may also earn extra point by gathering fish while avoiding a number of fatal hazards (falling in the water, snow geese, polar bears, etc). Success in this game requires a temporally extended plan to ensure the agent can accomplish a sub-goal (such as reaching an ice floe) and then safely proceed to the next sub-goal. Ultimately, once all of the pieces of the igloo are in place, the agent must proceed to the igloo and complete the level before time expires.

Frostbite Challenge, which was one of the control problems tackled by the DQN of Mnih et al3. The DQN learns to play Frostbite by combining a powerful pattern recognizer (a deep CNN) and a simple model-free reinforcement learning algorithm (Q-learning). Basically, taking the inputs by stacking images of last 4 frames (avoid temporal limitation) pass it through CNN to producing the output of action to take given the input. DQN uses techniques like experience replay (to avoid correlation) and seperate target Q-network to stabilise the performance. The DQN learns to map frames of pixels to a policy over small set of actions, and both mapping and policy are trained to optimize for long-term cumulative reward (the game score).

DQN may be learning to play Frostbite in a very different way than people do. One difference in amount of experience required to learning. In Minh et al, the DQN was compared with professional gamer who received approximately 2 hours of practice on each of 49 Atari games (although gamer had prior experience with some of the games). The DQN was trained on 200 million frames from each of games, which equals to approximately 924 hours of game time (about 38 days) or almost 500 times as much experience as the human recieved.

Problems in two challenges

One may argue that, “It is not that DQN and people are solving same task differently. They may be better seen as solving different tasks. Human learners -unlike DQN and many other deep learning systems -approach new problems armed with extensive prior experience. The human is encountering one in a years-long string of problems, with rich overlapping structure. Human as a result often have important domain-specific knowledge for these tasks, even before they begin. The DQN is starting completely from scratch.” Humans, after playing just a small number of games over a span of minutes, can understand the game and its goal well enough to perform better than deep networks do after almost a thousand hours of experience. Even more impressively, people understand enough to invent or accept new goals, generalize over changes to the input, and explain the game to others.

The challenge of buidling models of human learning and thinking then becomes:

- How do we bring to bear rich prior knowledge to learn new tasks and solve new problems so quickly?

- What form does that prior knowledge take, and how is it constructed, from some combination of inbuilt capacities and previous experiences?

- Why are people different?

- What core ingredients of human intelligence might the DQN and other machine learning methods be missing?

Core ingredients of human intelligence

Authors propose 3 core ingredients as one way to answer the problems questioned in above two challenges.

The 3 core ingredients are:

- Developmental start-up software

- Intuitive Physics

- Intuitive Psychology

- Learning as rapid model building

- Compositionality

- Causality

- Learning-to-learn

- Thinking Fast

- Approximate inference in structured models

- Model-based and model-free reinforcement learning

In the follow up post, we will go through each of the ingredients in-detail.

Happy Learning!

Footnotes

NOTE

Questions, comments, other feedback? E-mail the author